I am always changing

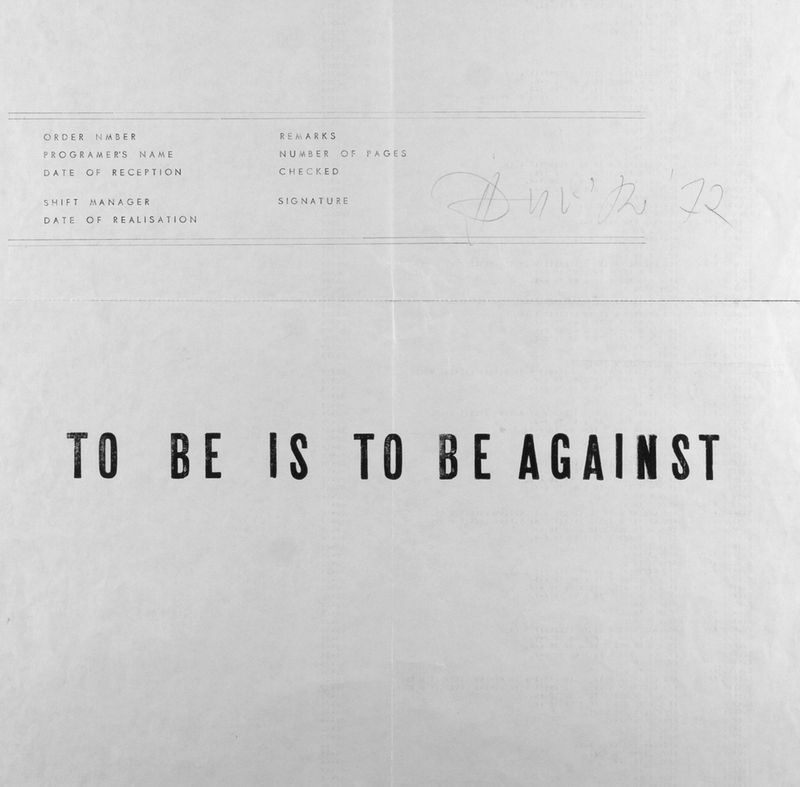

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, To be is to be against (detail), 1972

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, To be is to be against (detail), 1972Konrad Scheurmann

Flash Art PE, 1/1990

Changes, variations, and the course of processes – these are the phenomena he encompasses, using various means of artistic expression; analyzes, using strikingly simple means; and presents visually. In this way he achieves startling effects, conveying his uncommon visual experiences and attitudes.

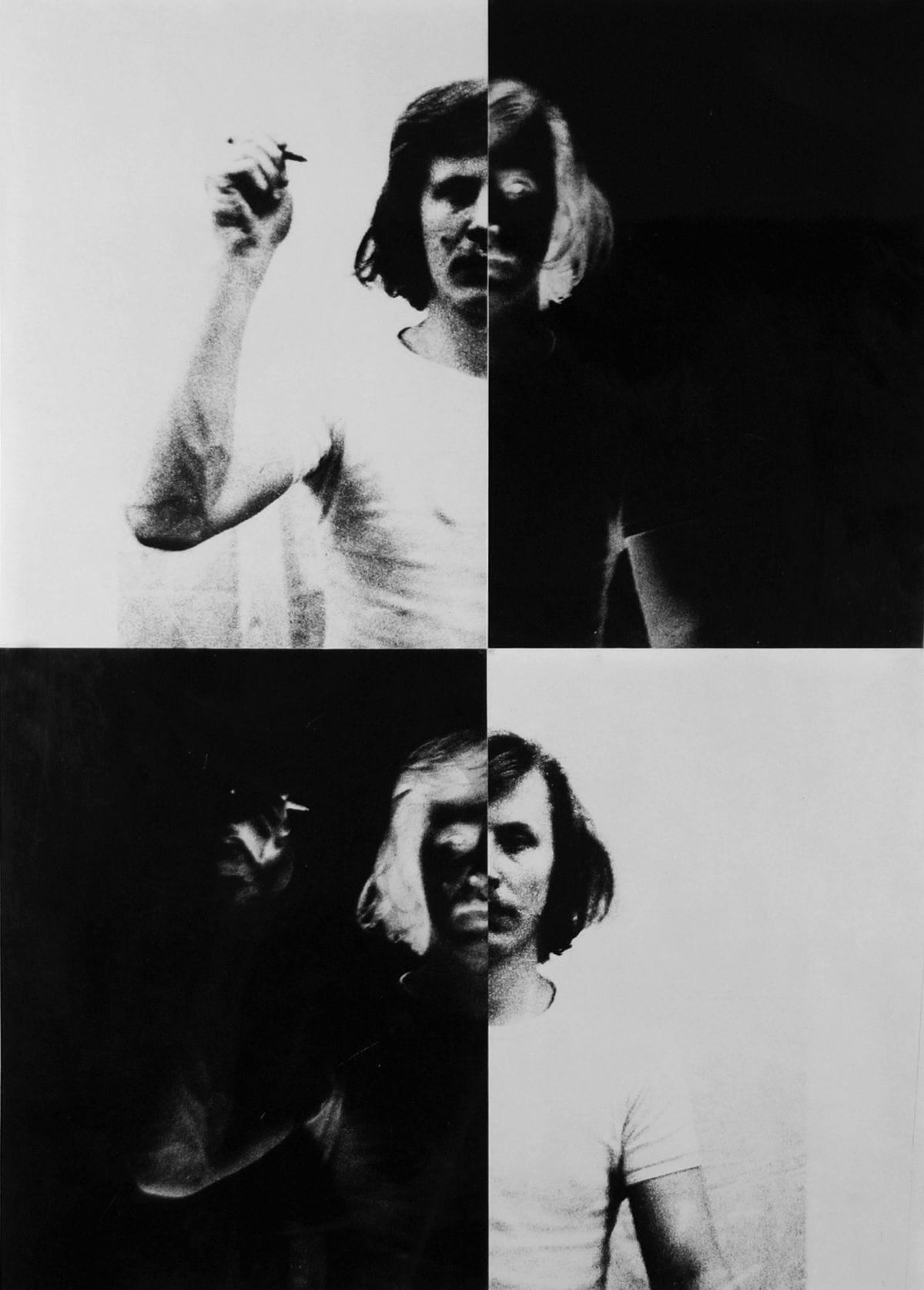

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Moment Art, Drawing Myself in Black and White, 1976

“I am always changing” – this statement, made by Duniko in 1972, is an uncommonly profound characterization of this artist's creative process, a process marked by enormous creative disquiet and constant openness to perception.

As the highest motto of his conceptual method of work, taken from a series of similar-sounding consciously ironic self-definitions, this statement also serves as an introduction for a thoughtful approach to his ever so variable creativity, and a comprehension of it, and especially of the central theme to which Duniko has devoted so many graphics series, room installations, pictures, sculptural works, and countless sketches and designs.

Changes, variations, and the course of processes – these are the phenomena he encompasses, using various means of artistic expression; analyzes, using strikingly simple means; and presents visually. In this way he achieves startling effects, conveying his uncommon visual experiences and attitudes. In a very particular way it is the dimension of time which fascinates Duniko; and this in no merely physical sense, but as the principle of all life, as a puzzle, at the heart of which lies the contrast between the physical incomprehensibility of time on the one hand, and its effects on the other, effects which reveal themselves in the ephemerality of all beings and all objects. The fact that time works, and how it works, is manifest in the traces it leaves behind.

His works, which since 1976 have been created under the title “Moment Art”, visualize these searchings in the most obvious way. He selects ordinary phenomena, entirely physical processes, such as the gurgling of liquids, floating chips of wood, the condensation of breath on glass. The choice of a process, the observation of its course, and the drawn, photographed, or plastic documentation of it become equally important phases of the work, culminating for the viewer only in the documentary effect, which is a sculpture, a sketch, or a photograph: a liquid, dripping onto plastic, flowing out over the edge of the vessel; a sequence of photographs of the artist's breath, condensed and concealing or revealing the artist's face as he blows on the glass; a drawing captured as a model in a shallow tub of water. These captured moments, these arrested fragments of time – the capturing of that which is in fact impossible to capture, which is to say, the deceptive game with traditional observation, provoking one to have it out with time, experienced as something obvious. Irritation and visual shock arouse a heightened susceptibility to a disquietingly different possible reality: for example, to the fact that even something which is traceless leaves a trace.

But this does not happen only in works from the “Moment Art” series. In the paperworks, too, time is the leading element, recognizable in the transformations, variations, and deliberate disruptions of sequential graphic structures. This process is depicted with particular delicacy and uncommon expressivity by the “Albums”, composed of many layers of Japanese paper of extraordinarily delicate structure. The initially imperceptible movement of the various modules (square, rectangular, or triangular segments of paper, variously tinted, partially stained), gradually grows stronger, and suddenly reveals simultaneously the nature of time and movement. The layered texture of many places of transparent paper, which is to say, the superimposition upon one another of specious processes of movement, additionally gives an impression of depth, equivalent to looking inside the work of art, an insight which by the effect of depth also suggests spatiality, and makes a two-dimensional work into a spatial object. The most convincing aspect of these paperworks is the fact that they achieve their action, included between the plane and the area of action, and their vibrant power of expression, not “out loud”, but rather in a very subtle way. It is rather as though one were to throw a rock into the water, and the concentric circles were to gather strength as they radiated outwards. “Albums” in fact “creates” such circles.

The works from the series “Projections” and “Notations”, printed on computer paper, draw upon similar perceptual experiences. These consist of layerings of building structures, or linear forms printed in color, one on top of another. Sometimes this printed surface is covered by delicate flakes of cotton – yet another possibility for creating a non-specific depth.

Duniko's art, in addition to analyzing the processes of time and movement, is still characterized by the concept of transparency. For his paperworks or foilworks, he most often uses transparent materials, which can be thought of as background or foundation. The expression “thought of as” makes us very much aware that the concept of transparency cannot be defined unambiguously. Often the deeper planes of the works are embraced by transparent planes that lie upon them; often, however, the deeper layers are only extracted by removing or scratching off the surface layer. It is precisely the series of large-format pictures – which, with their traces engraved on the canvas, can virtually be regarded as wall reliefs – which gives a fully expressive testimony to this analytical art, which is in a certain sense a kind of painterly archeology. In a similar way, the black, white, and red triptych from 1976, a document of just such an exploratory archeological work, shows on three tablets the traces of layers of paint that were once there, in the same color, but in a different order.

Insofar as the “Moment Art” series, and some of the paperworks as well, can be regarded as a formal game, so too the pictures, the wide-ranging series of drawings and sketches, and many of the paper collages, created in a virtual fury of work, are characterized by an enormous gesticulating power of expression, which all but physically emanates the internal disquiet of the artist, and his occasionally violent struggle with the theme and the material.

Gesture and graphic structure are often interconnected in many of Duniko's works. The thesis could even be advanced that a graphic concept is operative until the sculpture takes shape. Whether it be in the spatial installations, such as “Ready for Use”, or the figural works from the mid-1980s, or the oil paintings, everywhere we find Duniko's signature, that rapid line, full of expression, but also perceptibly nervous. The spatial installations, figures, and figural sketches display restless contours and internal structures; they are, as it were, at once under tension, in perpetual motion, sensitive and fragile. In the figural works, in particular, the lines or the plastic details defining the figure operate more as bundles of muscles or nerves laid bare than as a covering safely surrounding the figure.

This helplessness of the “picture” is maintained and supported by Dunikowksi in accordance with a certain simple, formal, perhaps unconscious decision. The majority of his works, and especially the large-format paper objects or the transparent foil pictures, are presented with frames, or as sculptures that cross over the dimensions of the surroundings, or virtually push themselves out from the wall into the space of the room. A breath of air, or the movement of air behind a person passing by, suffices to move them, even perhaps to change them.

Many of Duniko's works live in this ambivalent emanation, as though they found themselves in the center of the eternal axis of movement between movement and rest. The point of crystallization for one series of works lies in the experience of time, for another in space and movement.

A highly personal experience of ambivalence, and of the journey, so decisive for his later career, along the axis of his life, was formulated by Duniko at the beginning of the 1980s, in a series of spatial installations called “Ready for Use”. The time of exile, the political pressure, the uprooting, the protest – all this finds expression in the fragile ensembles of wood scraps, painted red, black, and white, stacks of flags bound up with cloths, bundles of brushwood, or graffiti written on the wall with mallets. The works appear to be so light and tottering that a moment's inattention could destroy the whole arrangement; and yet they still call to mind clubs ready to be used, demonstration banners, stakes: a journey along the axis that joins sensitivity to violence, two sides of a constantly recurring “medal”.

To this series of works – constituting a discussion of political power and the perverted power of not only of state authority, but of social authority as well (from the early 1980s), supplemented by a series of pictures reminiscent of flags, on paper and foil, entitled “New New Revolution”, a coming to terms with the emblematics of the state and with signs of authority – there corresponds a recently executed series of video installations, whose origins reach back to the 1970s. The temporal necessity to execute these installations can be found in society, which is now shaped by the media and is ever more susceptible to them.

“Current Program – Truth or Lies?” – this is the title of a series which, in the full sense of this word, puts the artist's theses and questions to discussion on the basis of the current television program being broadcast at a given moment. At first glance, this is an ironic play on the illusionary nature of the medium which is television, where no distinction can be made between fact and fiction, between reality and screenplay. But Duniko takes this one step further. To the extent that he draws himself and his work into the program, and understands the set as a part of his own staged apparatus, he also questions the work of art, ascribing to it, too, the inability to distinguish between the truth and lies. Ambivalence become ambiguity. While in the first of these there is still contained the possibility of being for or against it, the second leaves an uncertain impression, a feeling of “what would be if”, possibly of fraud. In this form Dunikowski describes very clearly, and with striking expressivity, the action of a media society, touching every aspect of life and stealing from it its own truth, and also its art.

Perhaps it is just in this way that we should understand the work for which the artist gathered bones from battlefields and areas touched by war around the world, and which, on the basis of the current program, he understands as his contribution to remembrance and documentation, in a year which – especially if one follows the media – has been remarkable for the disunity of a recollection promulgated in accordance with the demands of the media.

Truth or lies?

Info

The article was originally published in the catalog: “Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Retrospective – My best…”, BWA Gallery of Contemporary Art in Krakow, 1995