Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko. Current Program

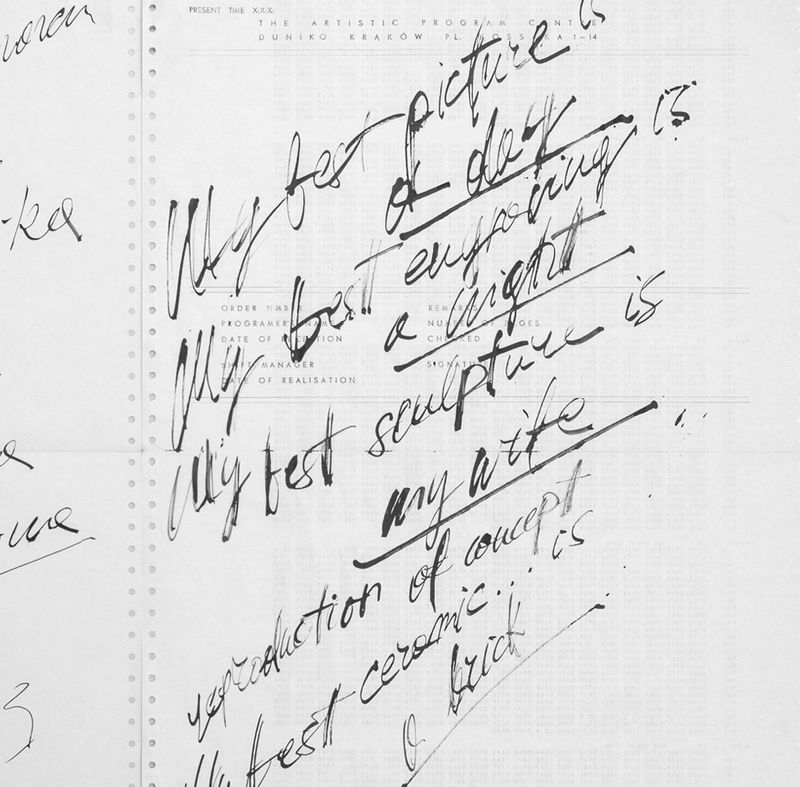

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, My best picture..., 1973

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, My best picture..., 1973Grzegorz Dziamski

O.pl Polish Culture Portal, 2006

“Dunikowski’s generation was the first generation in Polish art, which (...) had to find their place in the post-artistic age. It was the generation capable of seeing art everywhere. “My best picture is a day. My best engarving is a night...”

“I am always changing” – Dunikowski-Duniko says. This is the truth hardly to be questioned. The artist changes himself and so does his art. Though, this can be expressed differently – life itself is an on-going change and Dunikowski’s art has always striven to be close to life.

Many years ago the artist declared and he upholds this declaration that: “MY BEST PICTURE IS A DAY. MY BEST ENGRAVING IS NIGHT. MY BEST SCULPTURE IS MY WIFE” (1973). But is really Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko’s art a continuous change without any permanent points of reference?

Critics who wrote about Dunikowski’s art highlighted the artist’s interest in changes, variations, processes, time and temporariness (Konrad Scheurmann). They also pointed out that the sources of his art lie in conceptualism, or in the conceptual discipline – as Ryszard Stanisławski put it. Conceptualism still remains a mysterious area, not fully explored and continuously fascinating for new generations of the contemporary art scholars. This can be proved with such recent exhibitions as “Refleksja konceptualna w polskiej sztuce. Doświadczenie dyskursu: 1965-1975” /Conceptual Reflection in Polish Art. Experience of Discourse: 1965-1975/ (Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej, Warszawa, 1999), ”Live in Your Head: Concept and Experiment in Britain 1965-1975” (Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, 2000), “Probation Area. Versuchsfeld Arte Povera, Concept Art, Minimal Art, Land Art” (Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2002). The today’s art sources are placed in conceptualism and that is why Dunikowski’s art seems so attractive and so well tuned with the today’s spirit of time. However, what does it mean that Dunikowski’s art grows from conceptual art and that it gave rise to demiurgic and inventive imagination of the artist?

The curators of the London exhibition “Live in Your Head” claim that by the mid-1960s, most of the artists recognized later as conceptualists had internalized the precision and rigor of Minimalism. This, however, was merely a starting point because the truly conceptual art was a reaction against the Minimalist reductionism – a response that arose from the recognition of the unlimited potential of art. Works by Gilbert and George, Barry Flanagan, Bruce McLean, Hamish Fulton, Yoko Ono or Rose Finn-Kelcey transgressed the Minimalistic discipline and bravely entered into intimate relations with the reality, while not avoiding the moral and political provocation. This can be best illustrated with color photographs of Gilbert and George, presented as a banal couple of young Englishmen, which were furnished with the captions “George the cunt” and “Gilbert the shit” (the captions were removed when the prints were published in “Studio International” in 1970).

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Current Program XXVIII, 1983/1984

We encounter a very similar situation in the Polish art. In the mid-1960s, clearly crystallized conceptual or protoconceptual attitudes appeared, attitudes permeated with the Minimalist rigor: counted paintings by Roman Opałka (since 1965), visualisation of statistical distributions by Ryszard Winiarski (since 1966) and Minimalist forms by Zbigniew Gostomski, which led to the best known piece of Polish conceptual art “It Begins in Wrocław” (1970). These artists as well as many others, such Jerzy Rosołowicz, Edward Krasiński, Andrzej Matuszewski, Kajetan Sosnowski following the path of art’s self-purification arrived at pure, non-material idea of art. The early 70s, however, saw the entry of a new artistic generation for which conceptualism, for obvious reasons, was not a destination as for the artists of the older generation referred to above but rather a starting point, a kind of joyful artistic initiation. Conceptual art was for them “the revelation of creative potential at the stage of a dream.” These artists started to use the new, simple means of notation their ideas, photographs, drawings, texts not only because of their availability and simplicity but also, or rather primarily, because of their opposition against the approved view of art, its tasks, goals, values, means and forms. After all, it was the generation of counter-culture which approached the conceptualism as a means for clearing the art from false myths, redundant celebration, appearances accrued with time and also as a means allowing art to be closer to everyday life. Art and artistic activities were to become part of everyday life and something that would allow to live differently, to differently look at the world, at oneself and at other people. Dunikowski was one of the members of that movement, an active and committed one. Early 1970s saw an origination of many ideas which has been present across Dunikowski’s art: drawing on water, concert with TV sets, using a body for changing materials (melting the wax), red square against van Gogh’s sun flowers – ideas which confront the art history and at the same time introducing art to the everyday reality of a town, street, shop.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Ready for Use, 1982

Young artists entering the artistic stage in the early 1970s seriously approached the words of Jerzy Ludwiński, who wrote in his article “Art in Post-Artistic Age” (1970): “It is quite possible, however, that today we do not practise art any longer. Simply because we have missed the moment when it transformed into something quite different that we are unable to name. It is certain, however, that what we practise today presents greater possibilities.” Ludwiński called this new situation “art in post-artistic age” – where post-artistic indicates that everything can be art, and nothing, no object or event has to be art because the visual determination of art had disappeared. Artistic categories and criteria of assessment became useless and the notion of art fell to destruction, or – using a more figurative language – explosion, bringing it into many individual models of art.

Dunikowski’s generation was the first generation in Polish art, which had to face these challenges, had to find their place in the post-artistic age. It was the generation capable of seeing art everywhere. “MY BEST PICTURE IS DAY. MY BEST ENGARVING IS NIGHT….” Finally, it was the first generation, which was able to establish a totally non-institutional, fully alternative system of art because it could show its art everywhere.

Dunikowski participated actively in the artistic adventure of his generation. He took part in workshops, seminars and exhibitions, including a well known one “CDN – Prezentacje Sztuki Młodych” /CDN- Presentation of Young Art/, organized under the Poniatowski Bridge in Warsaw in 1977. He showed there his works from the series of the so called Moment Art. entitled “Duniko’s Breath” – it was a sequence of three photographs. On the first one, the artist holds a piece of glass at the level of his face; on the second – he registers his breath on the glass, and on the third photograph, his face is covered with glass misted over with his breath. This work has turned into a sign, an emblem of Dunikowski’s art and the artist reproduced it many times in his catalogues. No wonder – “Duniko’s Breath” can be considered the artist’s manifesto.

The breath of life, soul, something that the Greek called “pneuma” is a proof of life; we bring a piece of glass closer to the lips of an unconscious person as to check whether this person still breathes, whether he/she is still alive. For Aristotle, the pneuma was a link between the non-material spirit and material flesh, a link that conveys life energy form the flesh to the spirit and from the spirit to the flesh; for Stoics – it was a force reviving not only human bodies but the entire universe. Grasping the breath means to capture the simplest, the most ephemeral and transitory thing, and at the same time to praise life for the life sake – to live means to breathe. We live as long as we breathe, as long as we haven not given up the ghost, as long as pneuma keeps our limbs, our spirit and mind alive. The artist who covers himself with his breath is the artist concentrated on the energy of life, on art that grows from that life as naturally as breathing. The artist who draws with his finger in his breath is the artist who makes life the matter of his art (“Drawing in Breath”, 1976). The artist who along with his wife registers his breath on glass is the artist who incorporates his privacy into the area of art (“Joint Print with Breath”, 1980).

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Writing on Water, 1972

In the 1980s, Dunikowski’s art began to look different. The artist introduced materials, which he hardly ever used before. He enlarged the scale of his works and manifested more brave in annexing the space. At the exhibition “Stoffwechsel” (Kassel, 1982), i.e. the change in a material, he showed an installation called “State of Readiness” constructed with branches and twigs. They were painted white, red and black and were arranged in a rhythmical order, tied in bundles or covered with pieces of fabric and dust. Seemingly, everything has changed – the material, scale, means, yet the problem remained the same: how to capture an instant, moment, time? The work did not carry as intimate and personal meanings as registration of the artist’s own breath. For Ryszard Stanisławski, and not only for him, Dunikowski’s installation was associated with rolled up banners, ready to use truncheons, stakes to be set on fire, that is with a state of political alertness, with political picture of Poland during the marshal law (this association was further strengthened by colors used by the artist, though their meaning was more general, going far beyond the national and mourning symbolic representation). A moment underwent process of monumentalization. However, it was not only the moment of national history that was subject to such a process. Dunikowski monumentalized also his earlier photographic registrations of breath, which now assumed form of color sculptures (1981). Was it an ironic comment on the art self-mythologization? Or perhaps an ironic paraphrase of Goethe’s words “Verweile doch! du bist so schon!”

Can art capture ephemeral moments without falling into artistic mythologization? This was the question raised in the 1980s not only by Dunikowski, but also by other artists of his generation, e.g. Jarosław Kozłowski (in the series “Mythologies of Art.”). Is it possible to avoid the artistic mythology? Is it possible to find a place in-between the mythology of art and reality? Such questions prompted a birth of the installation formula that dominated Documenta in 1992 and a large portion of art on the turn of the 1980s. Installation had become a favorite form of expression for former conceptual artists. Joseph Kosuth said that installations were the expression of the artist’s attachment to a particular place and therefore they were shaped by a context, which can be architectonic, social, psychological, institutional or any other. Installation creates an “event context” whose meaning-effect stems from the spectator’s encounter with objects used by an artist in a particular place.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Self-mythologization of Art, 1974

Dunikowski’s art is such an encounter. Each time a different one because they are saturated with meanings of an individual place and because of expectations brought forward by the audience. The meaning of particular objects also changes – they are always incorporated into something that the artist calls a “current program” and which means that even older works or ideas of the artist gain new, updated sense in the course of such an encounter. Dunikowski does not get attached to meanings of his works, meanings, which would be agreed and fixed. When he says that his favorite program is a current program – one should believe him, regardless of how paradoxically that might sound.

Dunikowski’s exhibitions carry with them an atmosphere of a refurbishment; from the corners of his privacy the artist brings to light different works and ideas with a view to renewing their meanings in front of the audience. During the refurbishment everything gets moved, extracted from the former state, relocated. Nothing is certain and obvious. After some time, everything turns into normal – by the time of another refurbishment, which will make us look differently at what we had known so well. Refurbishment, occasional renovation of meanings is equally indispensable in our life as breathing.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Exhibition View: Kunstverein Heidelberg, Germany, 2001

Info

The article was originally published on the O.pl Polish Culture Portal on August 10, 2006.