Wincenty Dunikowski–Duniko and his Saturated Space

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Ready for Use, The Ark, 1980

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Ready for Use, The Ark, 1980Ryszard Stanisławski

Catalog “My Best...”, 1995

“Dunikowski’s works are by the intuitive factor of memory, passion, eternal return, by rejecting an idea and accepting it again, by the denial of what has been done, and especially by that very particular personal engagement of this artist, his aspiration, I would say, to risk and challenge.”

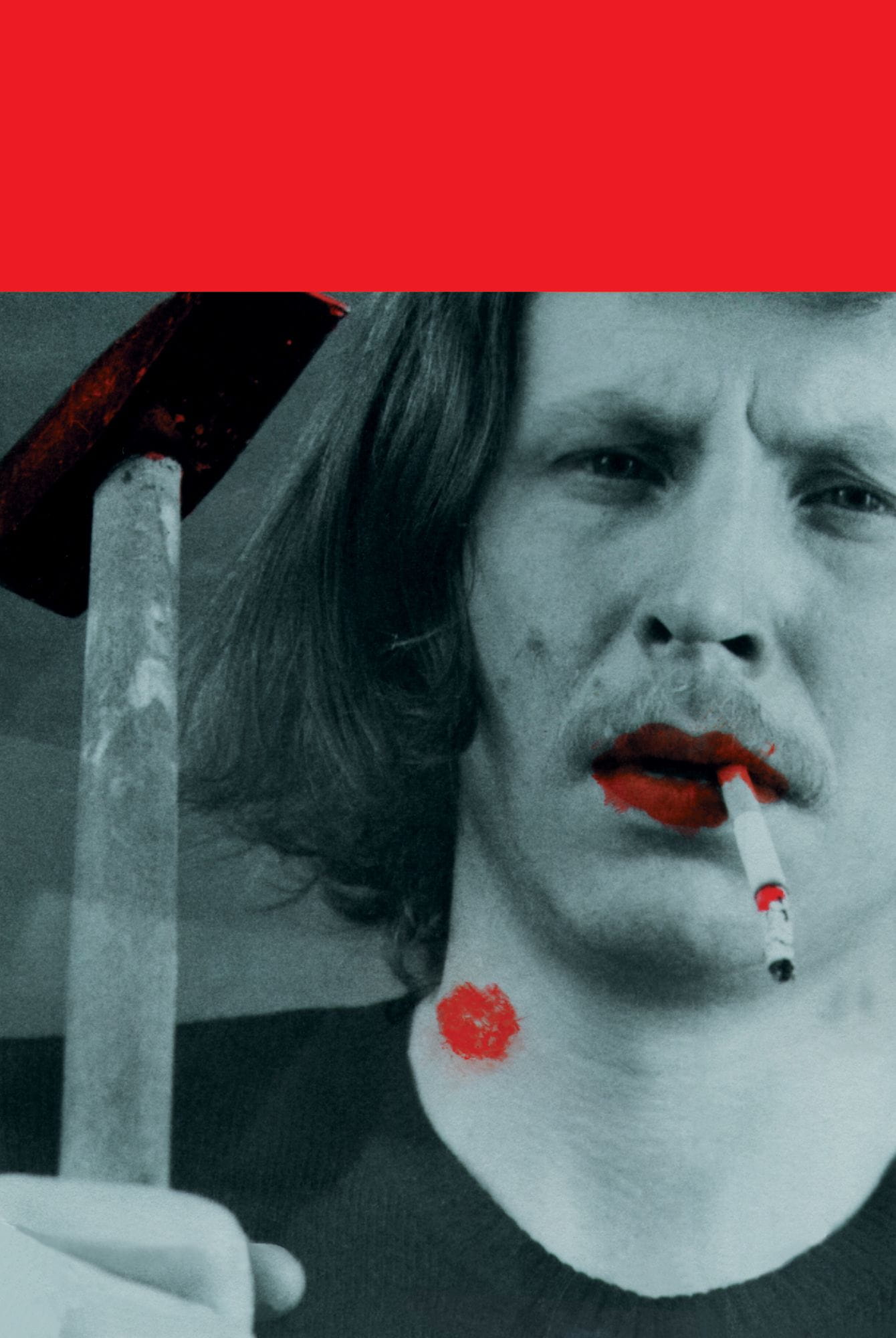

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Hammering Artist, 1976. In the collection of Mazovian Center for Contemporary Art “Elektrownia” in Radom

Two tendencies in artistic biographies can be distinguished in contemporary art. Some artists, like Bacon, remain faithful their entire lives to one poetics; other are perpetual seekers of new ideas, new vehicles, new materials and contexts. Here we shall occupy our-selves with the latter of these attitudes.

This takes its most convincing form when we encounter the leitmotiv of unceasing transformation, the spiral path of development, at an individual retrospective exhibition of a particular author.

The taking on of ever differing problems, from the radical individualism of an ephemeral gesture, to the application of rationalistic rules, such as those of computer art – this constitutes the driving force of the long careers of certain contemporary artists. One of these, in fact, has inspired these remarks with his current exhibition. It is just such a phenomenon that we encounter in the creative work of Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, a creativity which testifies to the ceaseless changeability and constantly active imagination of this author, and which leads him towards his own new worlds. This is confirmed by his exhibition, with all its wealth of startling propositions, executed in many poetics.

It is generally recognized (not entirely correctly) that the patron for artists of varying poetics is Joseph Beuys, from his manifesto of contemporary sculpture and the motto, “La rivoluzione siamo noi!”, to the scant traces, the registrations, shamanistic in their genesis, of the movement of animals, the multiples having gadgets for their motif, series of photographs of fetishes, ordinary objects, mechanisms with honey. It is also said that Robert Morris is their patron, from his falling felt sculptures, the metal bed connected to electrical current, to the monumental drawings executed with his eyes closed. Working in widely separated places, for some time not knowing each other personally, these artists of similar orientation, whose fundamental characteristic is unpredictability, go well beyond the asceticism of Marcel Duchamp, who in fact is also unpredictable on principle; they do so, since to Duchamp’s “work for the gray cells”, and to the submission to coincidence, which has a rational genesis, they have been adding, since the beginning of the 1970s, something perversely different. This is euphoria, at times fundamental social engagement, an element challenging egocentrism, the joy of modeling materials of “a lower order”, as Kantor would say, and perhaps also a theatrical factor. There is in principle no way to generalize these experiences, but they are paradoxically connected by that which cannot be connected: the constant dynamics of creative thought, the transformation both of one’s own behavior and the material on which one is working. The creative work of Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko is undoubtedly an outstanding example of these kinds of ideas.

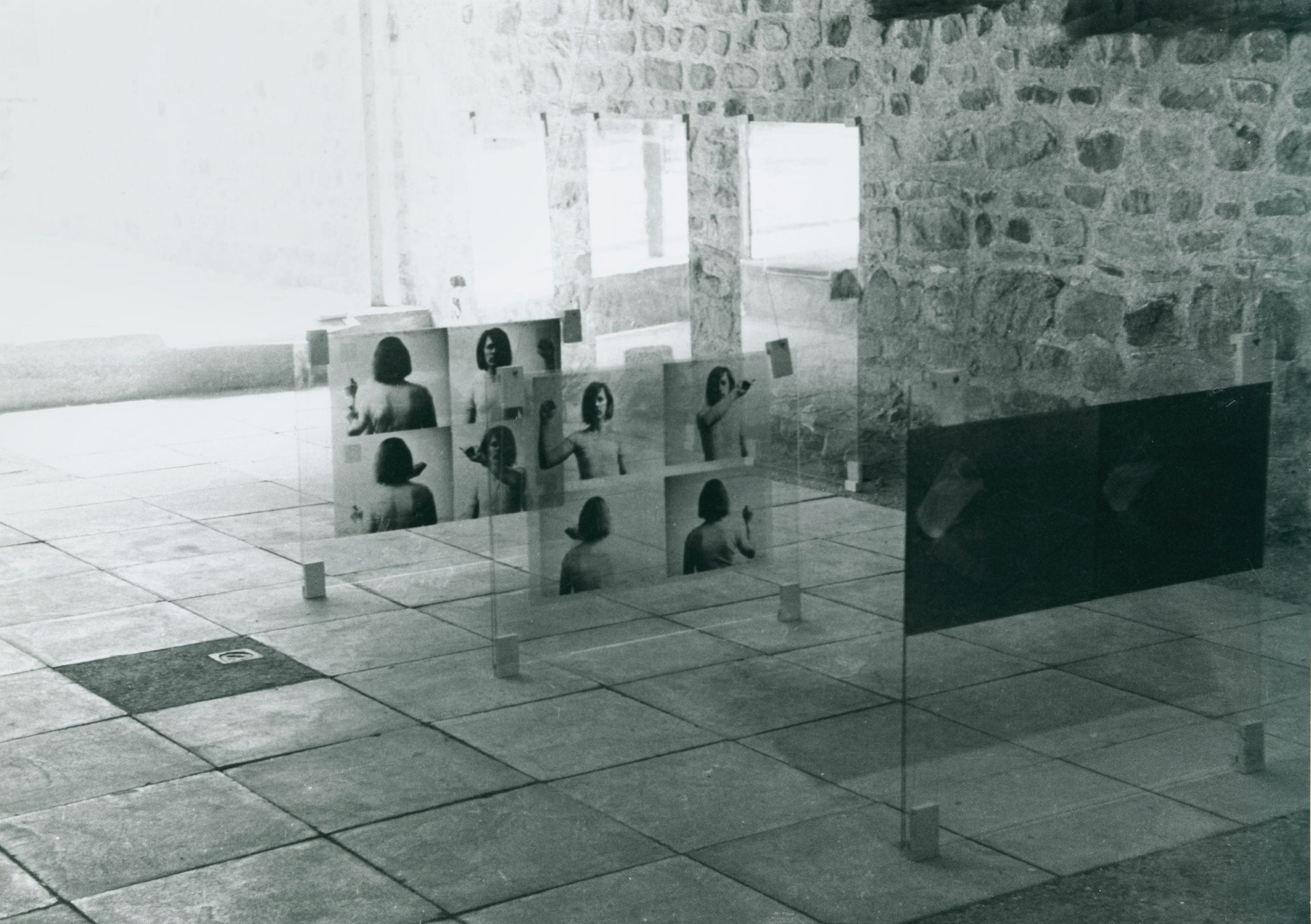

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Installation from the series Ready for Use, 1982 (Stoffwechsel K-18, Kassel, 1982)

If one were to mention an international sampling of all the artists of this particular type, it would turn out that the majority of them entered the world of art in the 1970s, and that those who in the 1990s are similarly using variable languages have taken a great deal, despite the difference in age, from the restless artists 20 years older.

It is conventional to regard the first half of the 1970s as the period of the domination of conceptual discipline; it should be acknowledged, however, that it is from this period, and not from the later painters’ trans-avantgarde or postmodernist chaos and “anything goes” indifferentism, that there emerged this fundamental posture of artists, imaginative, creative, inventive in the sphere of structures and public behavior, and remarkably independent. I am thinking here of those whose searches are both in the sphere of ideas and in the perverse functions of objects. Such a genesis for this dualism is confirmed by the works of Mario Merz, among others – to mention the particularly outstanding examples – and of the late Marcel Broodthaers, whose restless activity was particularly close to me; and here in Poland, the twenty-year-long career of Jarosław Kozłowski, and the difficult-to-sum-up work of Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko.

In the current creative work of the artists of this generation, I do not overestimate, as an absolutely decisive factor, the role played by the remarkably high aspirations of that ever more distant decade. As they have further developed, the artists of this now middle generation have not taken in only the written and experienced – non-artistic, super-artistic – readings and events of their youth. They constantly and consciously manifest their own inventiveness, opposed to the huckstering of the art of the 1980s, to its not infrequent conservatism and egocentric narrativity; and they also create their own repertoire, skeptically inclined towards the media hype of the 1990s. To be sure, current stimuli are not without significance; still, what is especially noticeable is the persistence of a certain unwritten rule, transtemporal for two decades: art has become a process, an act, a vector, whether it is directed “outwards” or is functioning “inwardly”, continually subject to various forces.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Ready for Use: Stitched Gallery, 1982. Exhibition: Ständige Bereitschaft, Kasseler Kunstverein, Kassel, Germany, 1982

The concept of the work, understood precisely as a constant and on-going process, can be exemplified by many succeeding works of Dunikowski-Duniko. Over the course of many years, he has been a creator who constantly rediscovers fields of interest, making the exhibition hall into a pulsating space of sparkling activity, contrasts, even arguments (if we assume that works can carry on this kind of dialogue among themselves).

I shall begin with a certain group of works bearing the common title “Ready for Use”, which at any event is certainly not the most recent. The objects ready for use, in the author’s interpretation, are not items of ordinary use, but rather symbolic objects, e.g. something like flags wound on the staff, or banners hidden in haste after an illegal demonstration, proclaiming a new faith. Their symbolism is not limited to the traces of red, black, and white, nervously thrown, so to speak, on a large canvas, but rather refers to the concept of “using” the work. Is the work, when it is wrapped up, only waiting for something? Is its definitive form, then, a classical configuration, when it is finally unfolded? But perhaps not. In my opinion, that readiness is the most important thing. Perhaps precisely this characteristic is becoming the property of the most essential moment of existence, transcending time, situated somewhere between the potential state and the demonstration, and in return between the demonstration and the state of potential energy.

It would be possible to consider other creations by Dunikowski from this perspective, even those for which, at first glance, it would be difficult to expect this property. I refer here, among other things, to many of the artist’s works originating in the 1970s, or to works that were at that time only conceptually designed: writing by the artist and the viewer with their fingers on the surface of water covered with sawdust, and “albums” with transparent sheets of paper covered with electronically printed geometrical shapes, ready to be repaginated in such a way as to change their configuration. I refer to long sheets with offprints in aquaforte technique on computer printout paper, which the viewer is invited to read. Finally, I refer to the works containing water, television monitors, thick colorful fluids pulsating in pipes. The dualism between readiness and fulfillment is also legible in the works on paper, those with cotton-like fog, with the trace of the painter’s gesture, as though unfinished, cast aside. They seem to be waiting for further continua-tion, possibly without any hope that they will someday be finished. The factor of hesitation and indefiniteness is contained in works where the rows of segments of branches and brushwood, set up at an angle, as though leaning against the walls of the hall, give no certainty as to whether they are supporting or supported.

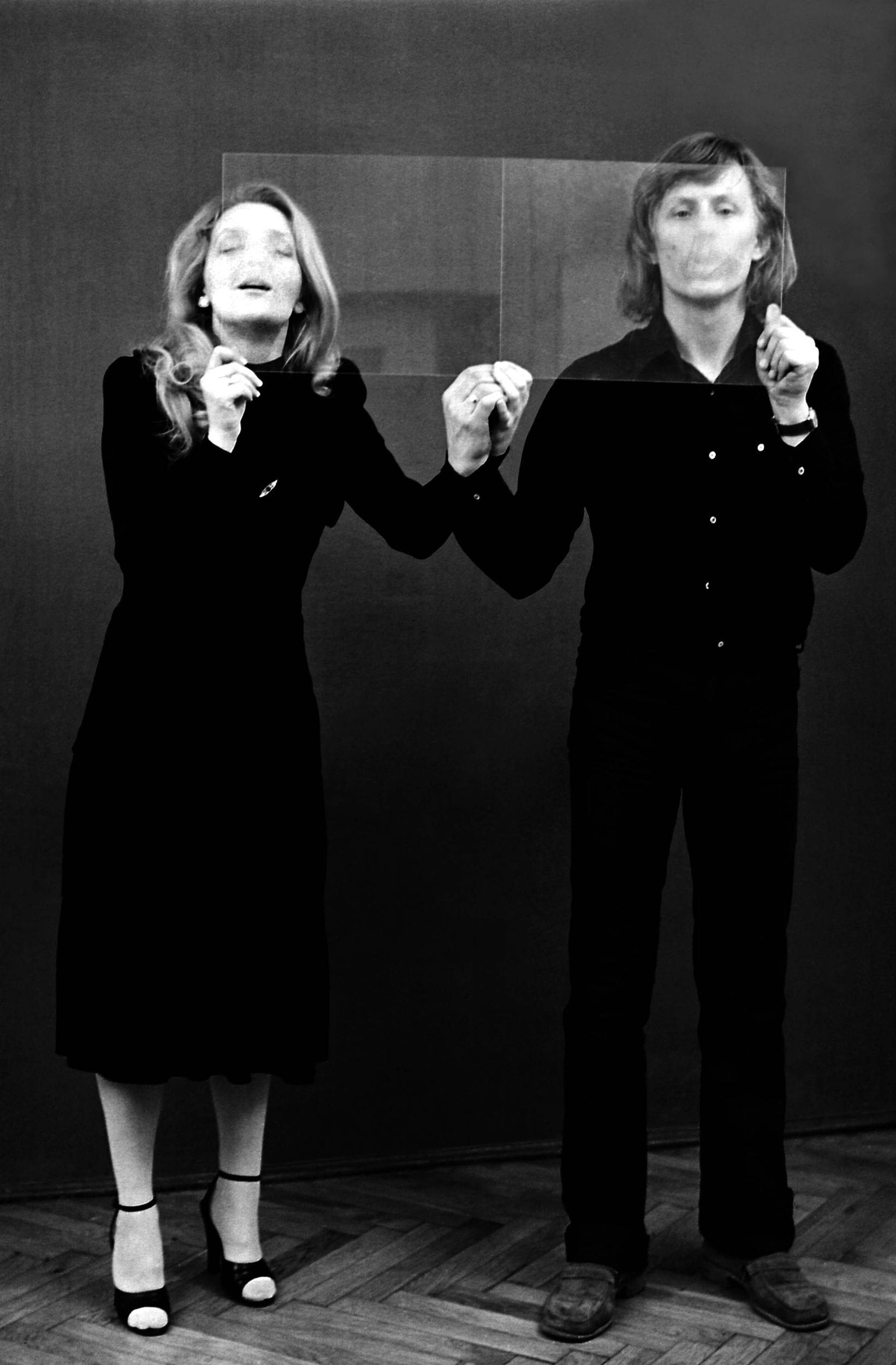

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Moment Art, Common printing with breath, 1980

Even the realizations from the “Moment Art” series, which a fortiori are displayed by the photo- graphic demonstration of facts and actions from the 1970s – the artist breathing out a fog which settles on a glass plate, the painting of pictures of his own face – also seem to be not so much a registration as a movement, a gesture, an intuitively actualized experience. And the works that border on sculpture, tottering structures with crutches, something along the order of drums, shrouds, and so forth, set or laid in irreproducible configurations, surely worked out on each occasion for exactly this exhibition, and no other – these seem to take on forms that are not definitive. The imperative to avoid something definitive – even if for obvious reasons it is not always observed – causes the space of the exhibition hall to become a whole, which speaks to the variability of the very nature of art.

It is possible to conclude that art – if we proceed further along the line of thought implied by the author – happens without systematization, without a “register”, since a museum register would confuse works with scaffolding poles left over after a repair, canvases with rags from the paint shop, sculptures with occasional tables, installations using monitors with a haphazard set from the storeroom, or a hillock of hay casting a vertical shadow with the raked-up remnants of mown grass. Such a mistake is, however, impossible.

Dunikowski’s works are connected by their strong emotional charge. They are connected by the intuitive factor of memory, passion, eternal return, by rejecting an idea and accepting it again, by the denial of what has been done, and especially by that very particular personal engagement of this artist, his aspiration, I would say, to risk and challenge.

Dunikowski accepts the situation where the viewer, surrounded by the objects created by the artist, may perhaps feel as though he were on the courtyard of some Far Eastern shrine: he does not read the contents of the objects according to the code he is accustomed to, but he comes to recognize the message sent, about permanence and impermanence, about a single moment and an extended span of time, about weight and lightness, about the revelation of a picture and its lurking in the twilight, about the active gesture and passivity. And above all else, about the fact that things and forces affect one another, together forming a cell charged with potential. For these are the components of human life, and not merely physical categories.

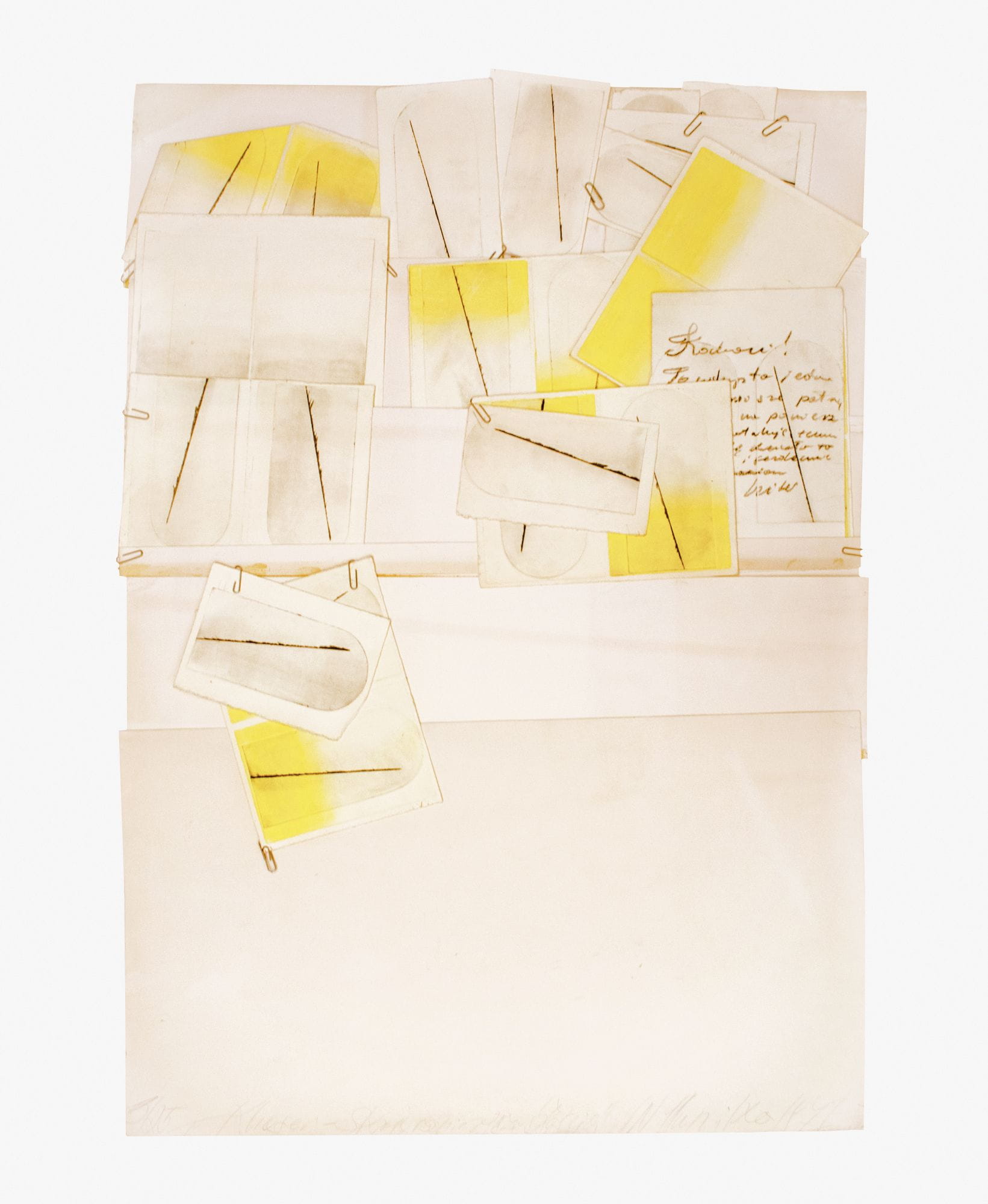

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Album I, Association with the past, 1972

Regarding other works – for instance, the labor intensive installation designs from the 1970s, not always completed at that time, in view of the then-current idea of conceptual prodigality – it could be said that they make physical laws and tools into some kind of an absurdity. The works from the series “Current Program” are not absurd in any unambiguous sense, since they are at the same time “angry” works, where the artist sets up monitors showing an actual television broadcast, or his own tapes, among distorting glasses, on a system of rocking springs; he orders the viewer to look at the screen through water, through fluids pulsating through pipes, reflected in a mirror, etc. This is a deliberate and intense intervention in that which is standard, required; or perhaps the oddness of a bantering rebel. The ideological sense of these works is legible, especially of those that were obviously set in contemporary historical time.

I was particularly intrigued by the design for the “Sunshine Sculpture”, which like many others has not as yet been realized. It certainly would lend itself to demonstration on an open space. This is a sort of configuration of two concave semipipes of considerable size, which, when correctly oriented, can focus light, be it sunlight or moonlight, on a third object set up between them (possibly a water mirror); as a result, this latter object seems to shine and glisten independently. This installation, which may superficially seem unlikely, and yet is entirely possible from the point of view of physics, can be imagined; the poetics implicit in the journey of light brought down to earth can be felt intuitively.

Dunikowski-Duniko poses us a puzzle, asking what is true and what false (a quotation from his notes and the titles of the works), and further asks whether the picture is more a delusion of the senses and a phenomenon of physics, or a fiction created by our longings. It is as though he wanted to test whether the object is only a transitory form of matter in the throes of transformations, or the relic of an event which can be explicated only with difficulty, and which on the surface seems dubious.

I would wish the artist and those who observe his works many moonlit nights under the sky of his native Kraków.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Works from the series Moment Art. Gallery Emonska Wrata, Ljubljana, 1979

Info

The article was originally published in the catalog: “Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Retrospective – My best…”, BWA Gallery of Contemporary Art in Krakow, 1995 and also in the catalog: Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Retrospective in Heidelberger Kunstverein, Heidelberg, Germany, 2001