Duniko — The Series

Krzysztof Siatka

Duniko.art, 2021

Review of Duniko's work based on selected series and projects — Albums / The Artistic Program Centre Duniko / Projections / Computer Series / Notations / Moment Art / Scratch Screens / Monochromes / Crumpled Screens / Scrap Books / Ready for Use / Flags / Foil and Foam Objects / New „New” Revolution / Current Program / Points of No Return / Utopian(?) Projects / Art Playing Table

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Album I, Association with the Past, 1972

Albums

Started in 1971, Albums consist of organic or geometrical modules arranged in rows whose linear pattern is occasionally disturbed in terms of rhythm, or layout. With these sequential structures concentrated mostly in the upper halves of the works, through partial overlapping the continuum appears disrupted or brought to a halt. Breaking with conventions, challenging the once established methods, or interfering with rhythms makes each of the created works unique. At the same time, large portions of the compositions left without any intervention amplify the expression of emptiness.

The titles hint at pages in albums intended for safekeeping precious prints, like stockbooks; the formal means employed, at the archival aesthetic, by connotation to institutions responsible for the processing of knowledge and the preparation of information. Metaphorically, the concept—whose visual outcome is perversely attractive—calls for artistic, political, and diurnal liberty.

In the seventies, postconceptual artists revisited, revised, and revived printmaking—it became an adequate language for self-referential renderings, a tendency promulgated by influential exhibitions (e.g. Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts). Albums count as Paper Art which—as the artist’s own classifier—underscores the natural qualities of the material. Assembled using the ‘no print prints’ method—that is, by stressing the processes of assembly, of folding, applying successive layers, gluing—these are not products of printing, yet they do constitute an integral part of those items (e.g. The Folded Sfumato, 1971).

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Album II a, 1972

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Be Right Back, 1972

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Album X, 1977

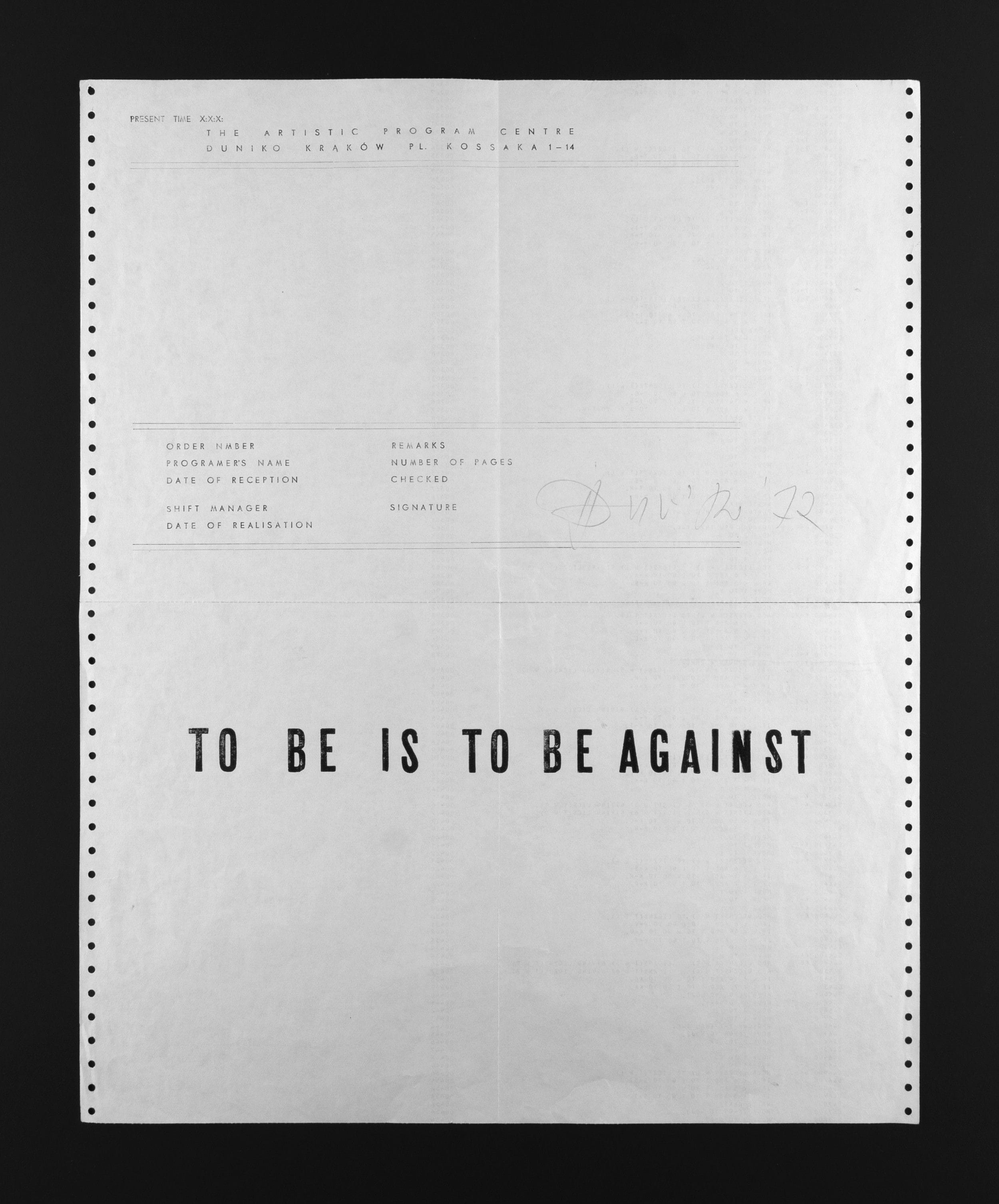

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Być znaczy być przeciw, 1972

The Artistic Program Centre Duniko

Established in 1972, The Artistic Program Centre Duniko served as a substitute for the author. The artist curated his brand following the examples of state-controlled manufacturing plants and science facilities. This branding involved above all the use of perforated computer paper, letterheaded “THE ARTISTIC PROGRAM CENTRE DUNIKO” as well as labelled for the purposes of classification and attribution (“ORDER NUMBER,” “DATE OF REALISATION,” “SIGNATURE,” etc.).

The Centre’s activities negated human effort as a prerequisite for the creation of works of art, extending the latter’s definition to include standardised aspects of a cybernetic aesthetic, and thus pointed to the possibility of having art produced by computers.

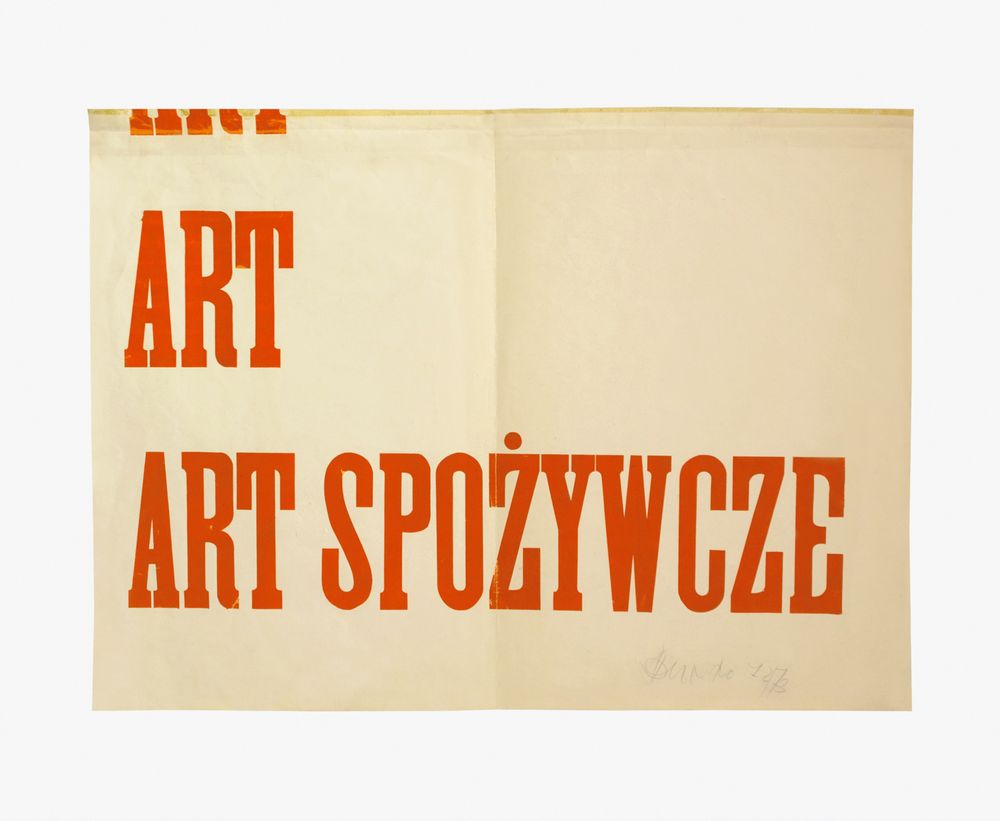

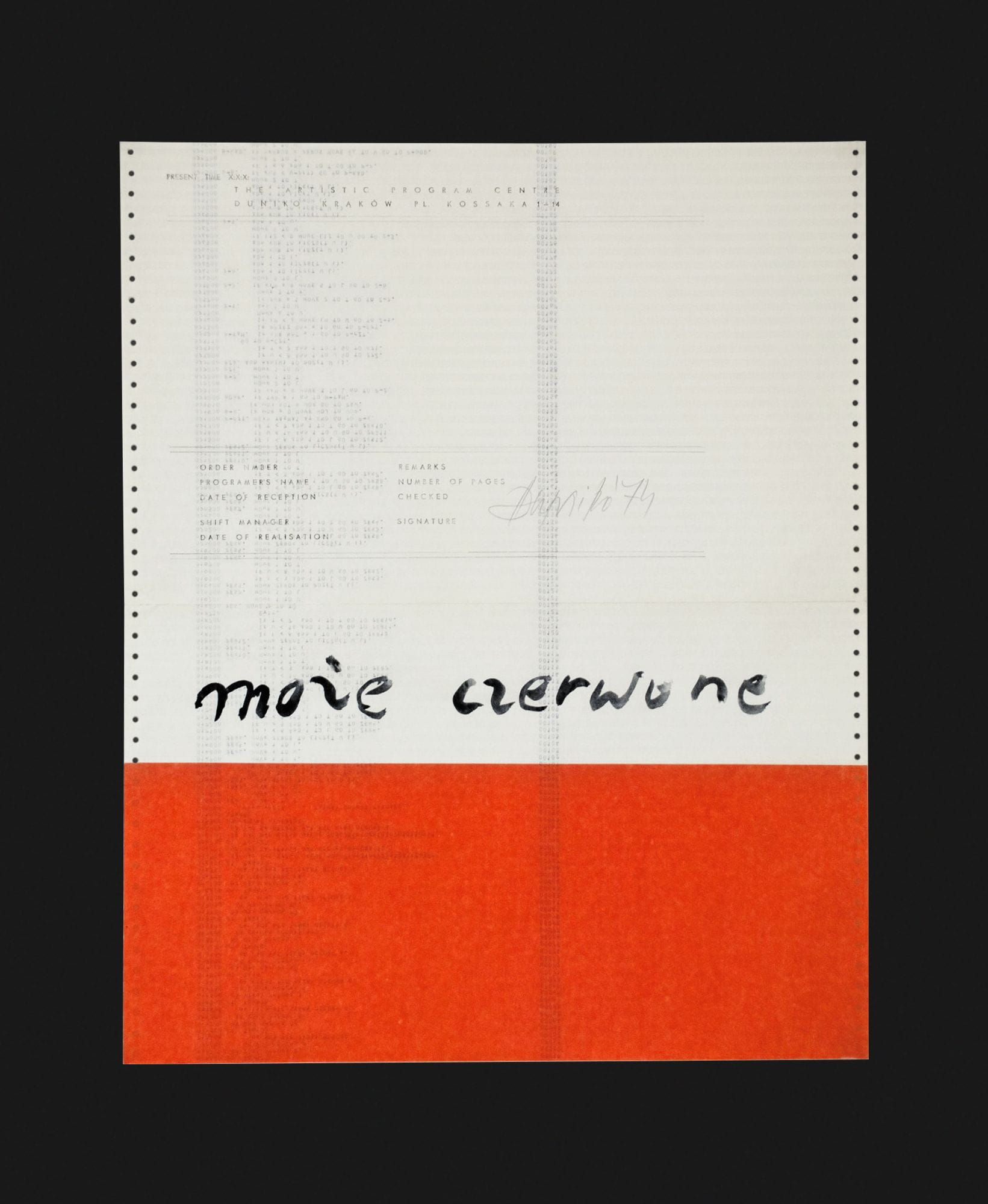

Mottos appeared in longhand or stamped on the Centre’s letterhead, stating the artist’s creative stance (TO BE IS TO BE AGAINST, 1972; TO BE IS TO BE DIFFERENT, 1972), becoming instructions for future political and ironical actions (an exhibition at the butcher’s: PRICE LIST, 1973, as well as ART ART ARTICLE *, 1973,; painting out street nameplates: LABYRINTH, 1973) and installations (MY BEST VIDEOTAPE IS CURRENT PROGRAMME, 1974), or forming original visual texts (MY BEST…, 1973).

* The Polish title, ART ART SPOŻYWCZE, plays with the ambiguity of the word art, denoting — as an abbreviation of artykuły and combined with spożywcze — groceries or foodstuffs.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Action: Labyrinth, Painting the plates with street names, Nowa Ruda, 1973

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Art Art Spożywcze (aka Art Art Article), 1972

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Może czerwone, 1974

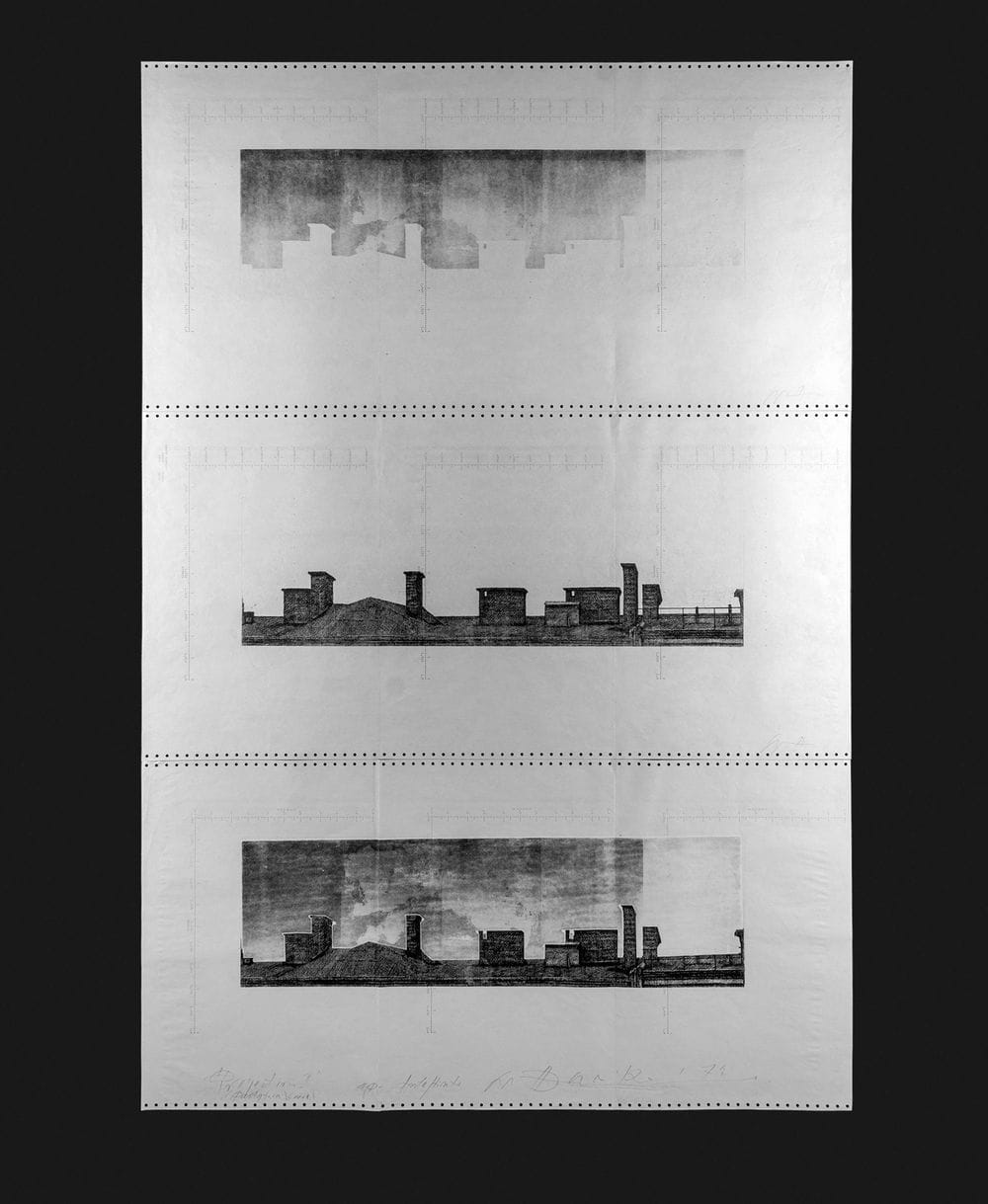

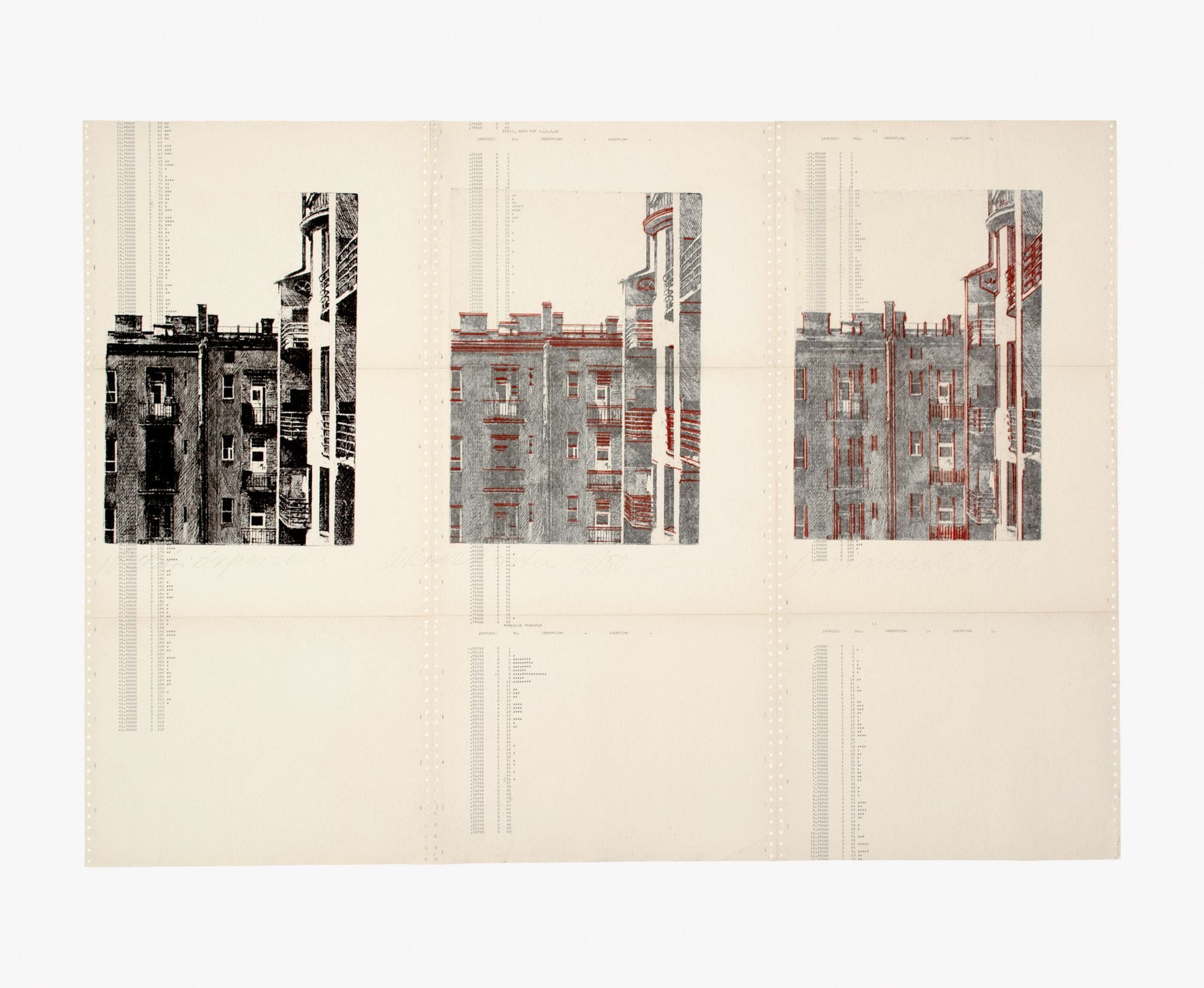

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Projection V, 1975

Projections

Every element of the works comprising this series, which began in 1973, shows a manipulation of an otherwise true-to-life image of a façade. The artist made copies of abstract excerpts from buildings, and added appliqués or used an original halftone process. The resulting narrative structure of a polyptych resembles the deconstructive approach to design. In terms of depiction, Projections illustrate potential events on a one-to-one scale — chunks of reality as well as effects of artistic interventions.

The series combines printmaking with cybernetics. The drawings on etching plates, composed of crosses or asterisks, resembled the product of a dot matrix printer. Projections emerged from the process of impressing perforated computer paper with still-wet prints. In the late seventies the etchings — intermediate products of the process — found use in many other works (e.g. The Point, 1974/1975; Pure Colour, 1974/1975; The One-Balled, 1974/1975).

Projection II – Detached Sky, 1974

Duniko's presentation of works from the Projection series, Academy of Fine Arts, 1974

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Projection – Partitioning of the Landscape, 1974

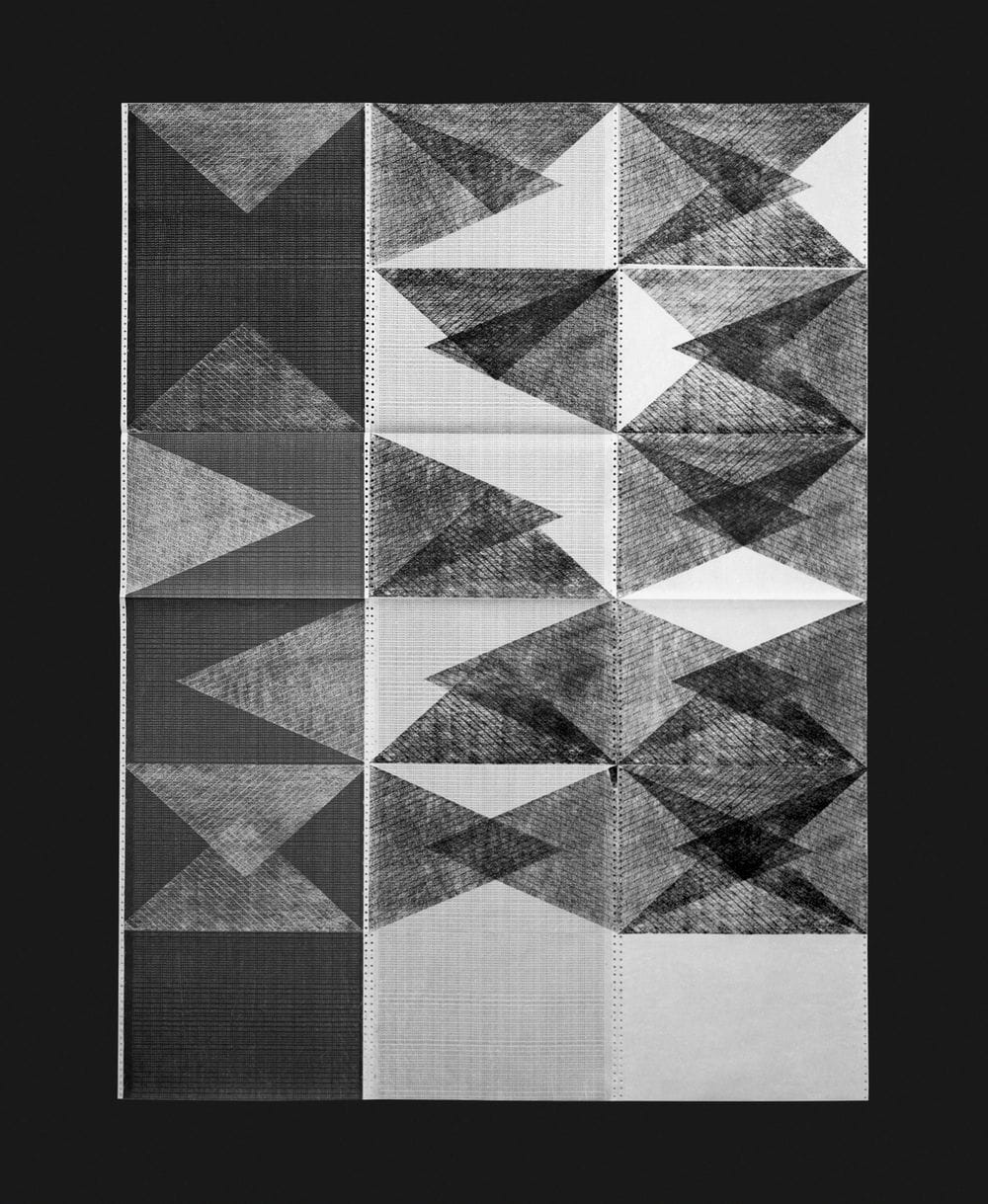

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Trójkąty. System zapisu, 1975

Computer Series

From 1972, using perforated computer paper, the artist developed an original formula for works comprised of two layers: the primary one derived from the non-artistic realm — prints from an Odra computer were used — while the secondary one, different each time that method recurred, was dictated by the author’s intention. In these works, discernible portions of code — either programmed as per the artist’s concept or random — appear along with prints or handwritten texts.

The use of computer paper, featured in numerous concurrent series (Paper Art, Projections, Notations, and The Artistic Program Centre Duniko prints, among others), is to be seen as exhibiting an ambivalent fascination with computers being employed in the creative process. In 1972, for the work titled Album A, Duniko commissioned an idiosyncratic computer program: the resulting perforated card — the data carrier of that time — contained a useless record, non-conformant to the rules of coding grammar followed by programmers.

The multiplied sequence “KRAJOBRAZ KOMPUTEROWY” (as in the title: Computer Landscape, 1974), also generated by interfering in the operation of the computer, and the landscape drawing, lithographically reproduced in the lower part of the tapes, exemplify a tautological method employing image and text. Resemblance to mathematical formulae, understood in the artistic process as principles of operation of the medium or determinants of the artist’s proceedings, can also be found in the Notations series — these were printed with alternating plates, on computer paper as well (e.g. System of Notations, Triangles, 1979).

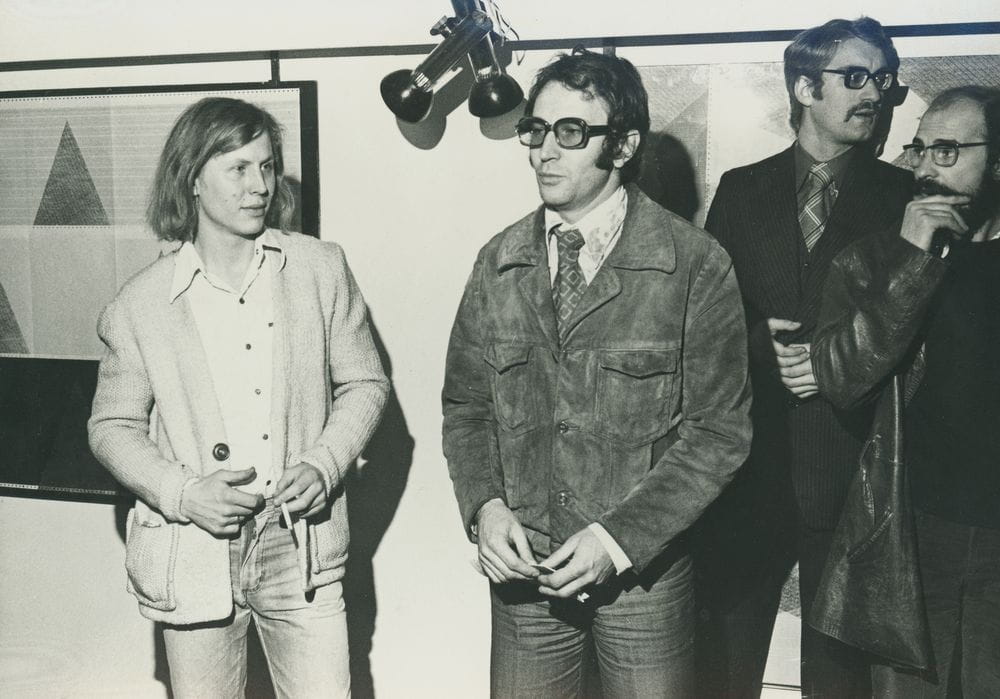

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Opening of the individual exhibition entitled Dunikowski-Duniko at the B Gallery in Krakow, 1975. In the photo from the left: Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Andrzej Pollo, Maciej Gurgul and Marek Nałęcz-Nieniewski. In the background: Triangles, System of Notation, 1975

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Computer Landscape, 1974

System of Notations, Triangles, 1979

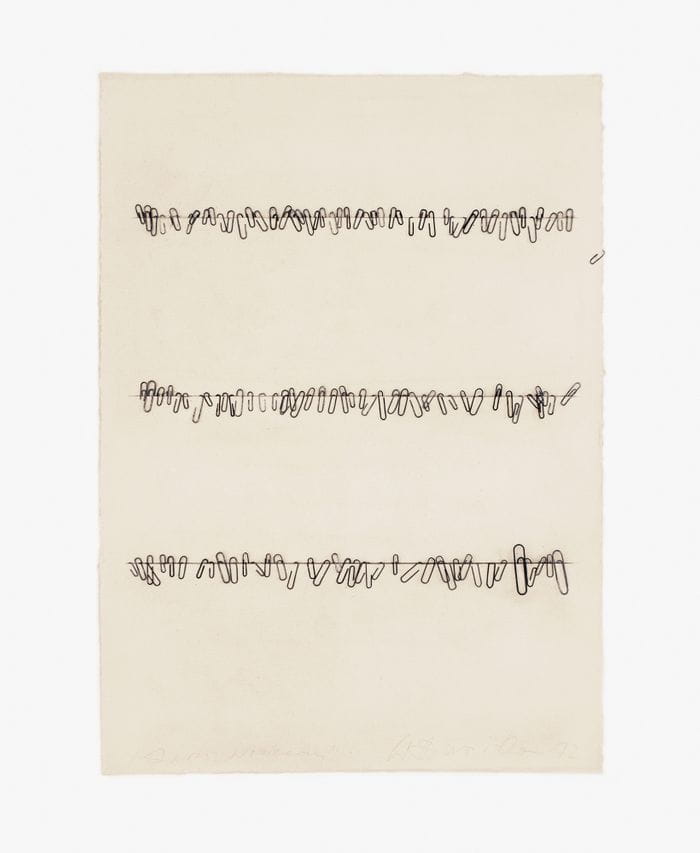

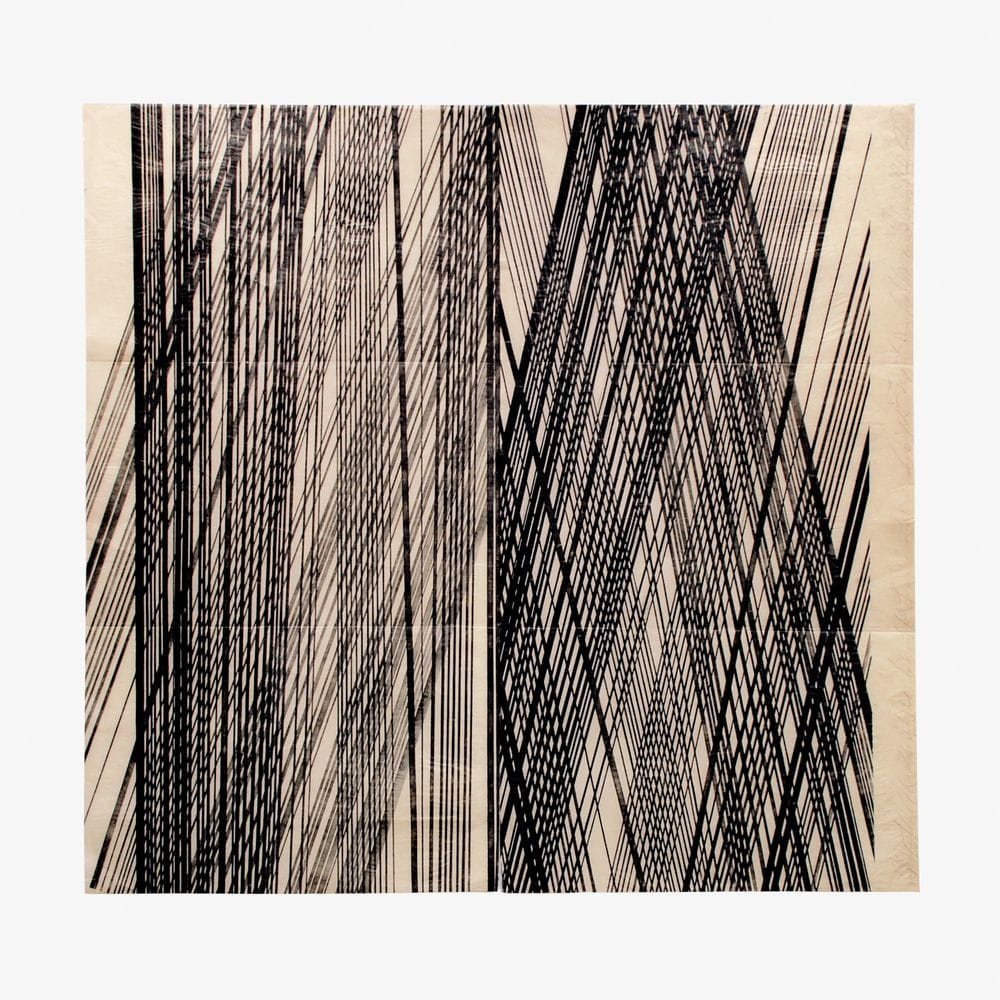

Notations

The works from this series, initiated in 1975, typically resulted from the use of two relief printing matrices — the simple dash- or slash-based motifs arranged thereon, of irregular thickness, established an antithetical relationship. In a process thus defined, printing on translucent paper produced highly dynamic images composed of patterns crossing at various angles and with varying frequency.

Resembling faulty structures, these abstract depictions — outcomes of an essentially anti-printmaking method — allowed readings, on the one hand, in terms of exploration or representation of imprinting, and on the other, concerning the emphasis on errors present in a fixed notational system (System of Notations, 1975). Several Notations were printed using a stencil, partially covering the matrix and thus allowing to obtain regular shapes. Consequently, the series has been extended to include allusive themes (Truncated Pyramids, 1976) as well as quotations.

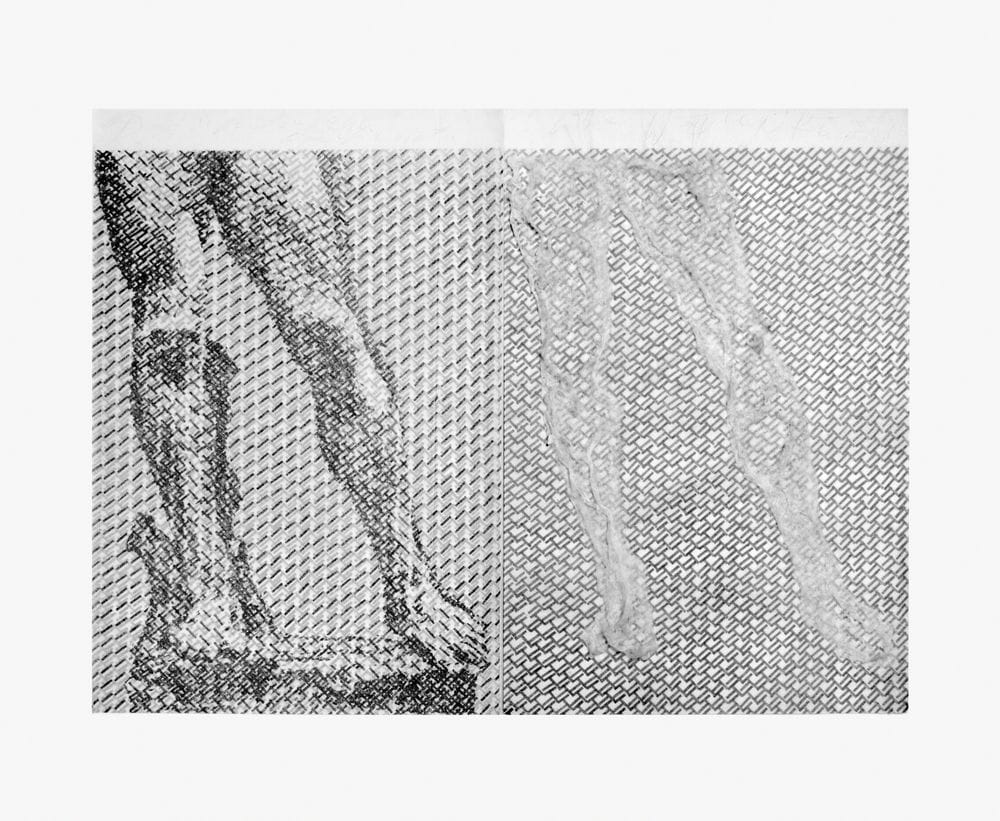

Nogi z waty Dawida (1975), for instance, is a rastered image of Michelangelo’s famous statue, with cotton wool applied. The work is an ironic take on the Polish idiomatic expression mieć nogi jak z waty (‘when your legs feel like jelly’; the noun wata translates as ‘cotton wool’): in its delicacy, and also in the lability of the substance, one could see the antithesis of what had traditionally been characteristic of a sculptor’s labour — of the hard work of carving blocks of marble.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Nogi z waty Dawida, 1975

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, System of Notation (B), 1975

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Oddech Duniko, 1976

Moment Art

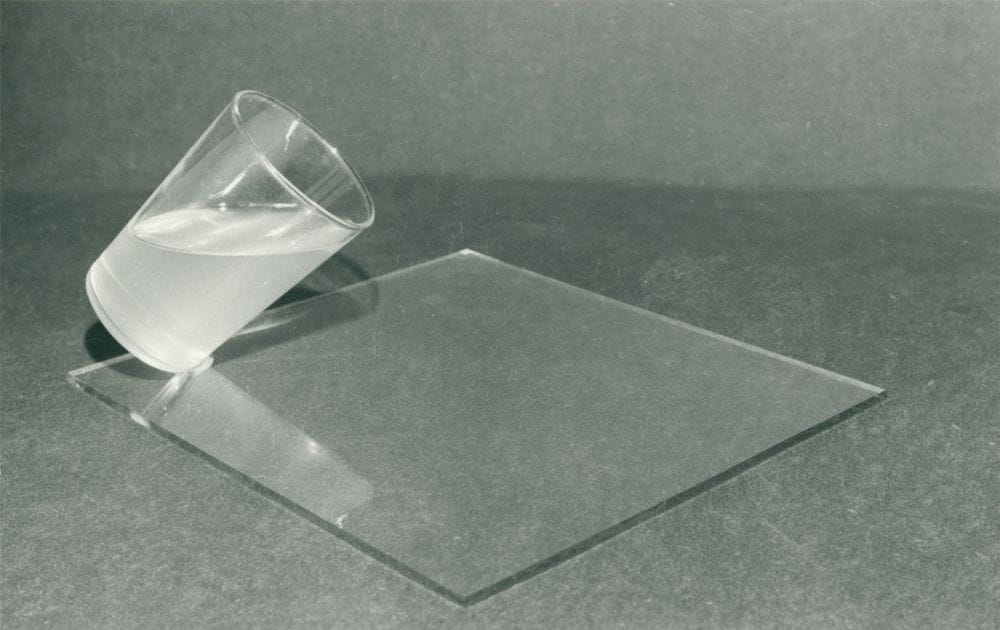

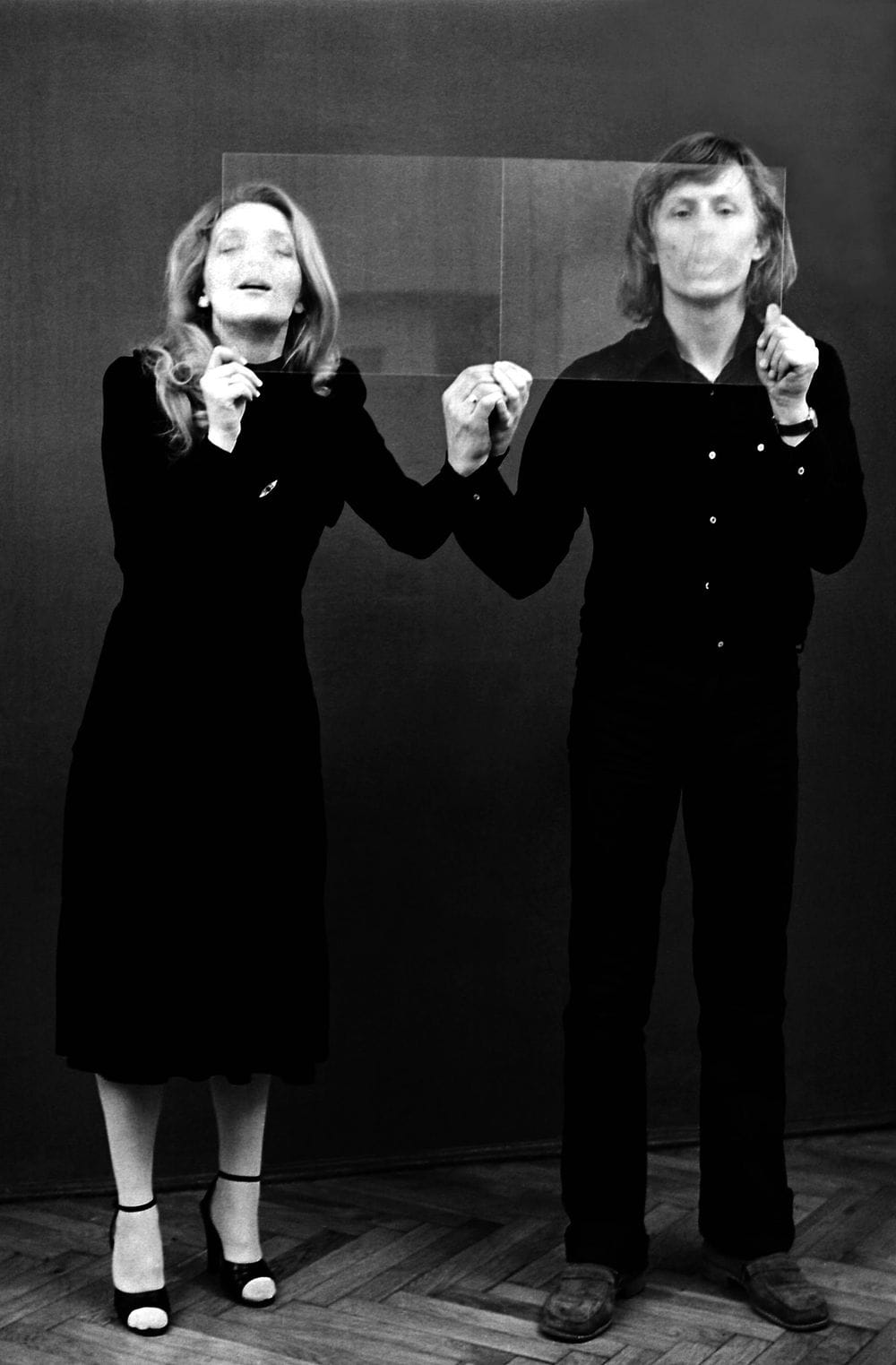

In 1976 the artist devised a novel formula for representing moments abstracted from trivial processes — their fleeting embedment in the present is what makes the Moment Art series unique. Ephemeral events captured in translucent photographs, such as a glass of water tipping over (Moment Art — The Hold II: Glass, 1974–1976) or a reflection in a bubble (Moment Art: Bubble, 1974–1976), significantly democratise the thematic scope of art. Sources of similar interests can be traced back to 1972, when action-oriented projects were conceived, including those of writing on sawdust-covered water with a stick (Writing on Water, 1972) or tensioning an elastic fabric while balls roll across its surface (Trampoline, 1972).

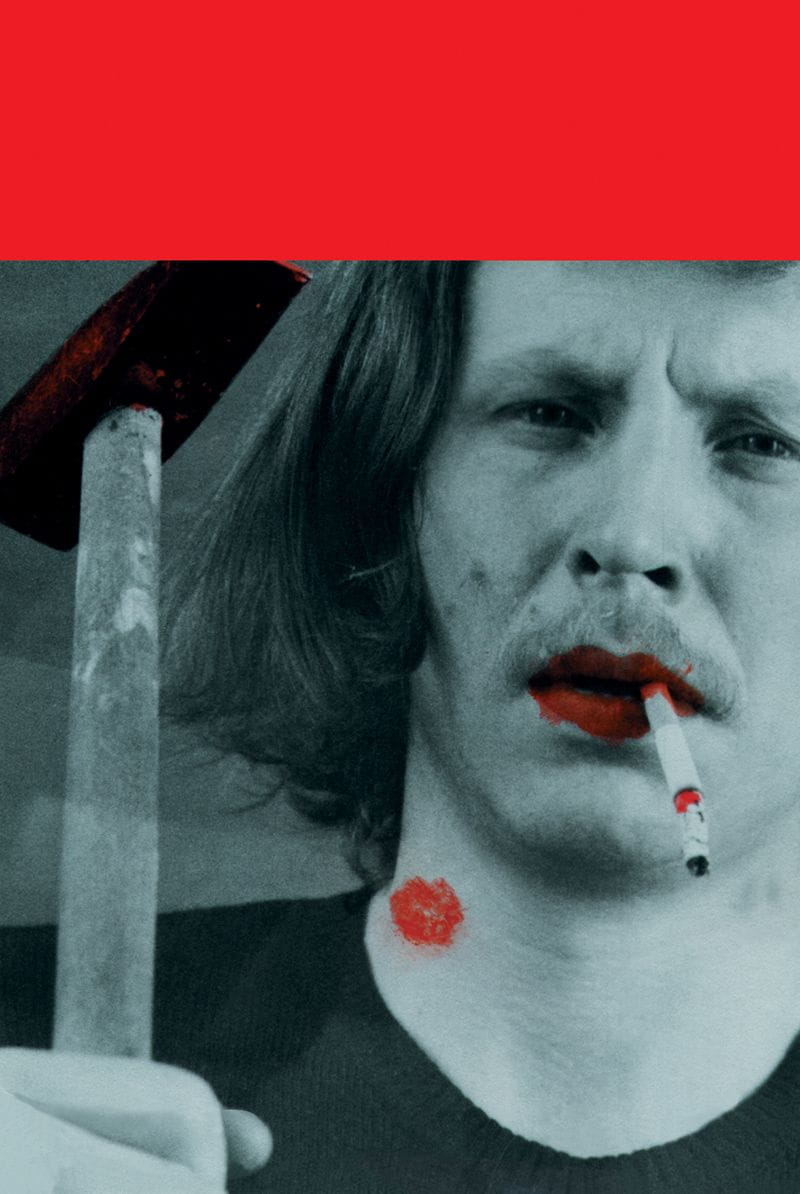

The principles governing the concept for Moment Art trivialise the ethos of an artist’s work and equate his actions with life processes. Similarly, the now expanded field of art may extend over excerpts from purely mechanical activities (e.g. Hammering Artist, 1976).

At the same time, Moment Art is a self-reflective reiteration of Dunikowski’s motto I am always changing (1972). Among emblematic instances of using this method are the photographic sequences depicting breaths (Duniko’s Breath, 1974/1976, or the more intimate Common Printing with Breath, 1980). In a number of works, the author’s portrait was de-composed, fragmented, and multiplied so that the posing artist gave the impression of manipulating the compositional elements of the image (e.g. The Hold, 1976, or Drawing in Breath II, 1979) — this way the author explored how his own body was entangled in the rules of its representation.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Glass, 1974/1976

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Common Printing with Breath, 1980

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Rysowanie w oddechu, 1976

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Hammering Artist, 1976

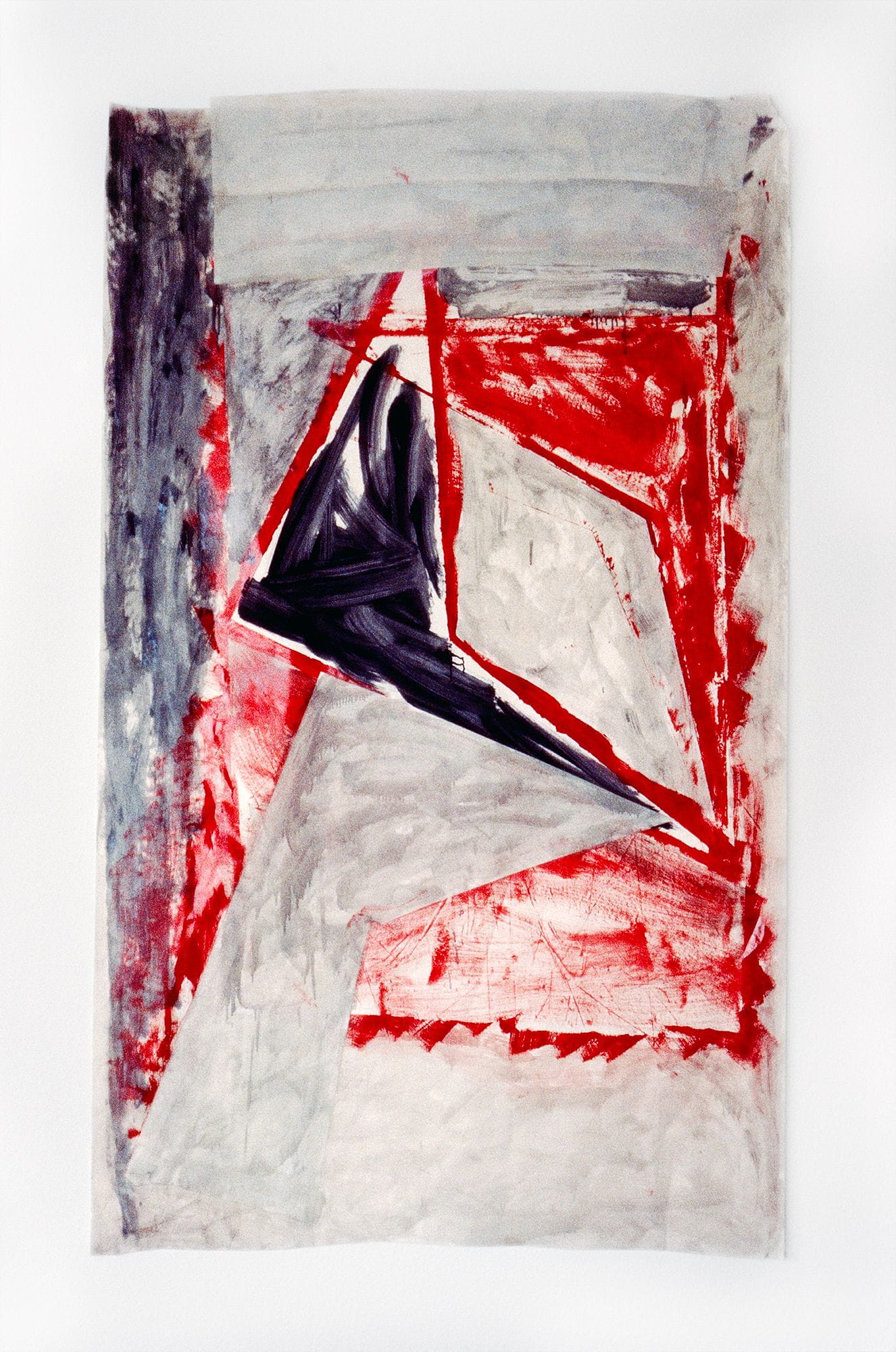

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Scratched Pyramid, 1982

Scratch Screens

The idea to use scratched materials dates back to 1977, when trials with soft etching paper were made. Soon after, a series of monochromatic works titled Scratch Screens was produced, highlighting mutilations of the monumental screens’ spongy surface.

The scratches on a single-colour plane, resulting from the use of a garden fork in a swinging gesture, became an allusive mark (e.g. Scratch Pyramid, 1982).

The emphasis laid on the application of a highly specific tool, which in drastic circumstances could be wielded as a weapon, inscribes the structure of the object with traces of how it came into existence — as well as agitates for reusage.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Scratch, 1983

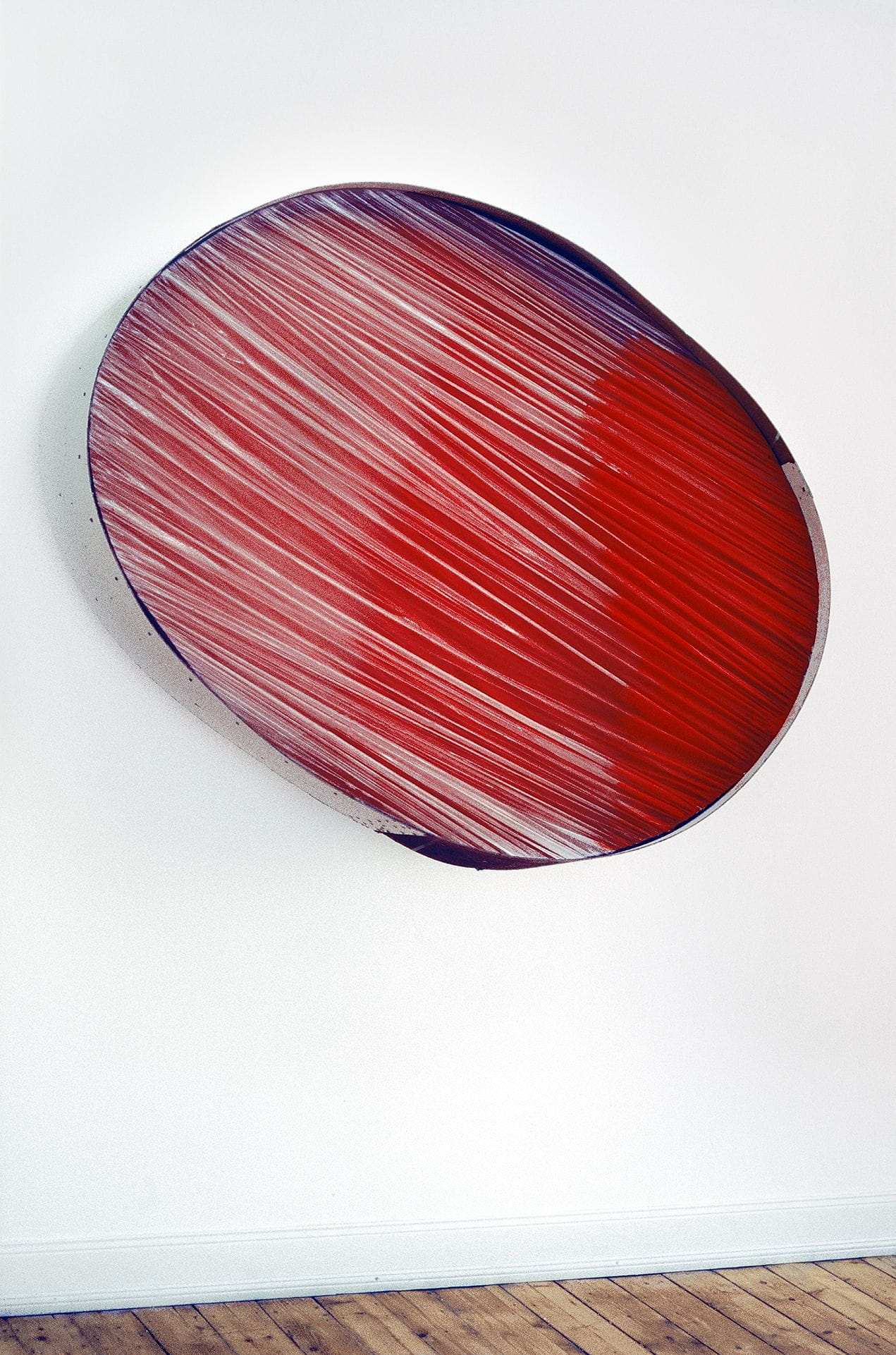

Monochromes

The artist first used monochromatically painted surfaces as early as in the late sixties, working on sketches for Moving Monochromes (1968), which would be an installation consisting of single-colour canvases stretched between two rolls rotating at a very low rate in order to constantly shift the minimalist planes. This established a certain property of his later monochromatic works, the perception of which is different each time mainly due to how space and time are experienced, and to a lesser extent because of their materiality. The final stage of that journey, apparently, was the 1995 project titled Pure Light, Pure Love, Pure Death, where space permanently annexed by colour acquires meaning in the process of perceiving it.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Hanging Monochromes, 1980

The creation of Monochromes, which started in 1978, consisted in the use of semi-opaque paint, only partially absorbed by paper: as the works cannot dry completely, they exist in a permanent state of emergence, never formed definitively. Losing the original properties of liquids and solids respectively, the materialities of paint and paper have translated into coloured and at the same time translucent formations of planes, unable to be stored or displayed in a manner applicable to other two-dimensional works: they are fragile and fragrant, and their shiny surfaces interact with lighting to induce diametrically different experiences of colour tones.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Hanging Monochromes, 1980. Solo Exhibition, Marina-Dinkler-Galerie Berlin, Kassel, Germany, 1982

The works from this series were sometimes hung with only one corner affixed, so that they naturally formed an array of conical spirals (Hanging Monochromes, 1980). The impossibility of displaying any of them again in exactly the same way manifested the expansion of the formulas of printmaking and painting towards spatial objects, and called for a reassessment of the related exhibiting systems.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Crumpled Screens, 1978

Crumpled Screens

Crumpled Screens is a series of abstract works created since 1978 by crumpling, tearing, ripping up, and reassembling large, pre-printed or shiningly painted sheets of wrapping paper. The ground — intentionally destroyed — and the coating — monotonous but wet and oily — both strongly stimulate the senses; none of the two layers seems more significant than the other.

The works stress the principle of reversion — construction by destruction — which also manifested itself in Scratch Screens. The aesthetic potential of material otherwise likely deemed wasted came to be reaffirmed by shows where deliberate protrusion or tilt of works hung on the walls voiced a wish, on the one hand, to annex the third dimension, and on the other — and perhaps crucially — to reassess ‘good taste’ and exhibiting conventions.

In most of these works the artist used a palette narrowed down to three colours — black, red, and white — which connects the concept to certain other series (especially Ready for Use, 1982).

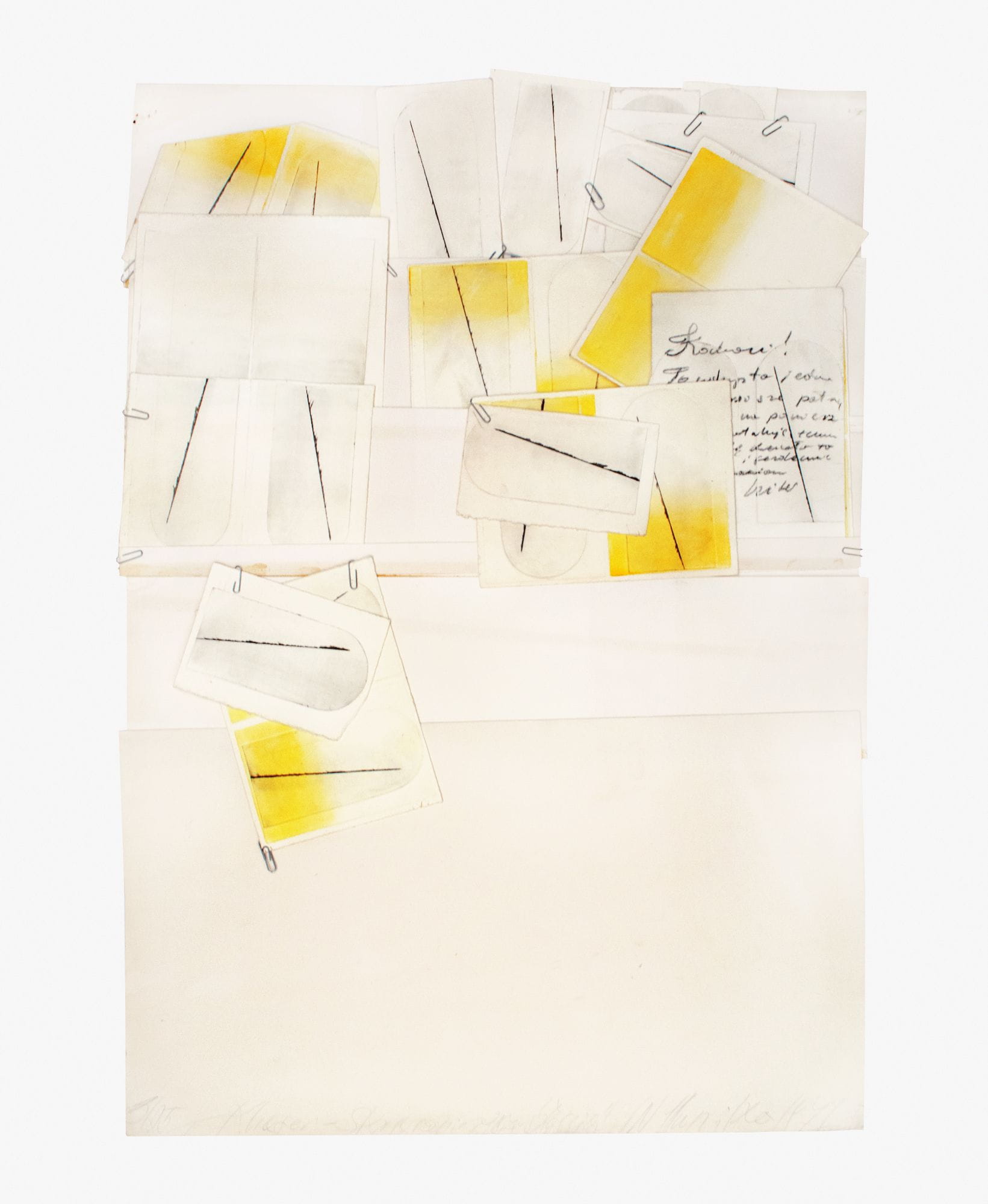

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Scrap Book I, 1980

Scrap Books

Developed since 1980, the group of objects jointly referred to as Scrap Books evoke pages of a notebook where clippings of any kind are kept: newspaper or magazine articles, photographs, dried plants, ornaments, et cetera.

While the abstract configurations of monochromatic prints and drawings in greyscales make use of the qualities of translucent Japanese blotting paper, the physical manipulations — folding, overlapping, or masking — are analogous to those performed in such other series as Albums and Crumpled Screens.

Anchoring their narrative axes in the attributes of paper, Scrap Books represent what the artist termed Paper Art. Their materiality is marked with the specificity of substance and, in equal measure, with emphasised traces of procedures employed as part of the original ‘no print prints’ method. Physically, the works take the form of irregular spatial objects whose structures are based on geometrical grids.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Scrap Book IV, 1980

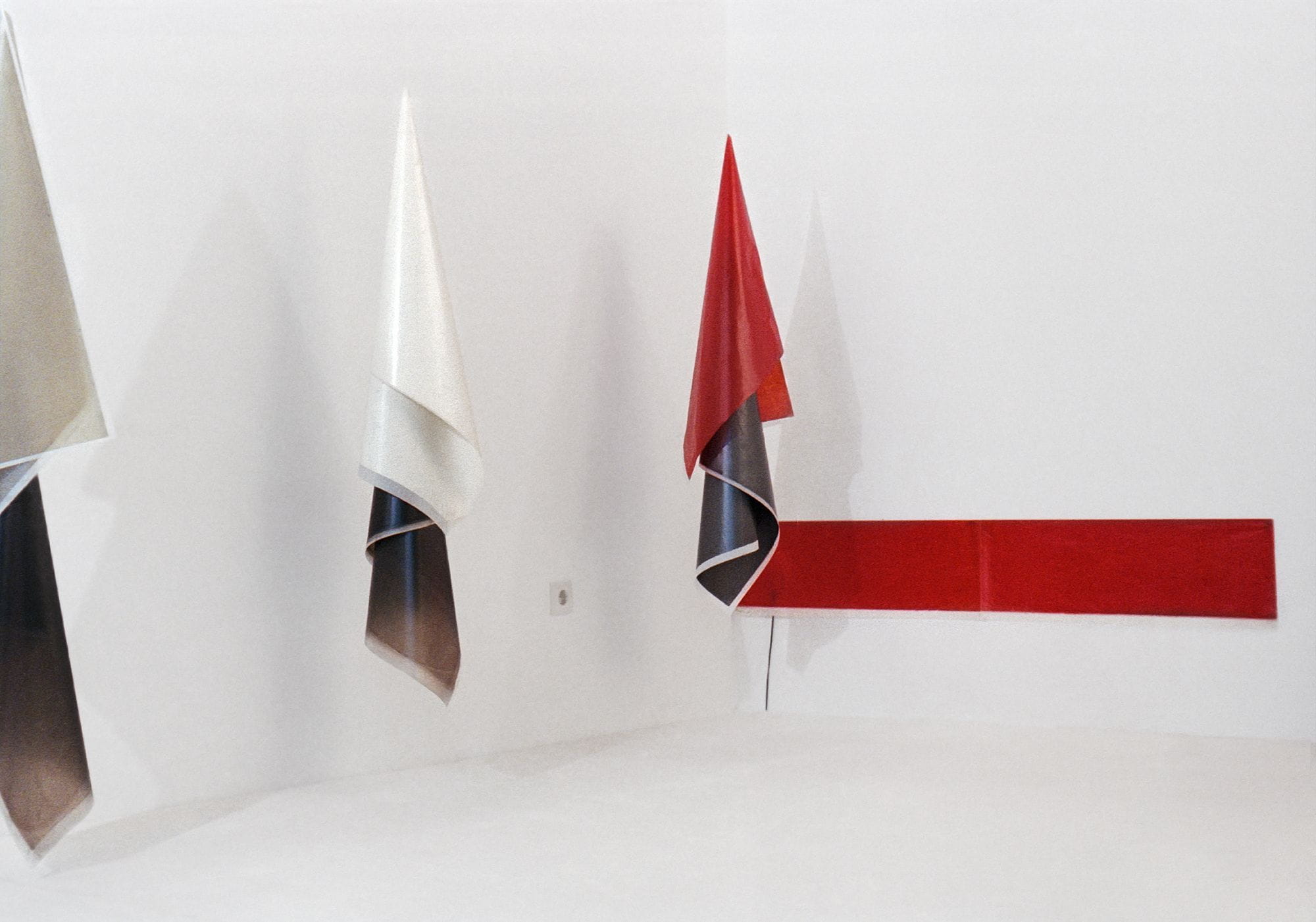

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Installation from the series Ready for Use, Stoffwechsel K-18, Kassel, Germany, 1982

Ready for Use

The concept for the site-specific installations jointly known as Ready for Use dates back to 1980. The artist used tree branches and trunks painted white, red, and black and similar glossy foil applications. The form of these extraordinarily expressive objects conjures up an abandoned or stranded ark, or a forsaken warehouse full of dust-covered standards or banner poles.

The prop motifs, taken from the non-artistic reality, represent an implied repository of readily available weapons, symbols of power, and life-saving appliances. Initially titled Permanent Readiness, the series comprises allusive elements of identification and means of uniting communities in a state of extreme danger.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Man with a Flag, 1984. Rosenheimer Kunstverein, Germany (1985)

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Installation from the series Ready for use, Stoffwechsel K18, Kassel, Germany, 1982

The most notable presentation of Ready for Use took place at the Stoffwechsel show in 1982, accompanying the documenta 7 in Kassel: this was the artist’s largest realisation abroad, right after leaving the country and upon the introduction of martial law in Poland, which — alongside the characteristic, oppressive atmosphere of the arranged spaces — only intensified the political interpretations of the works. Also in the following years the artist did not refrain from direct references to symbols derived from the political realm (e.g. The Red Square Folded, 1984).

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Man with a flag, 1984

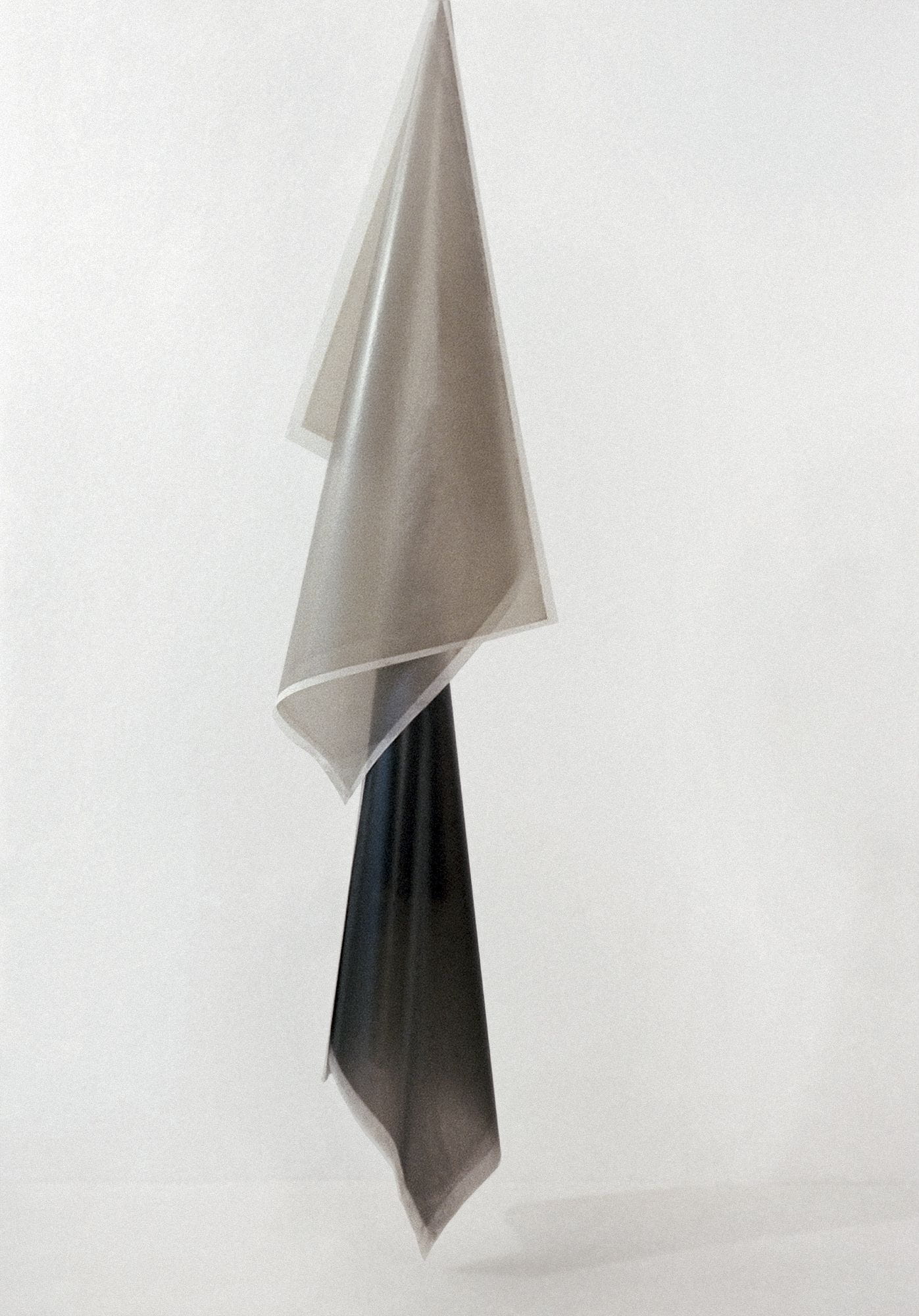

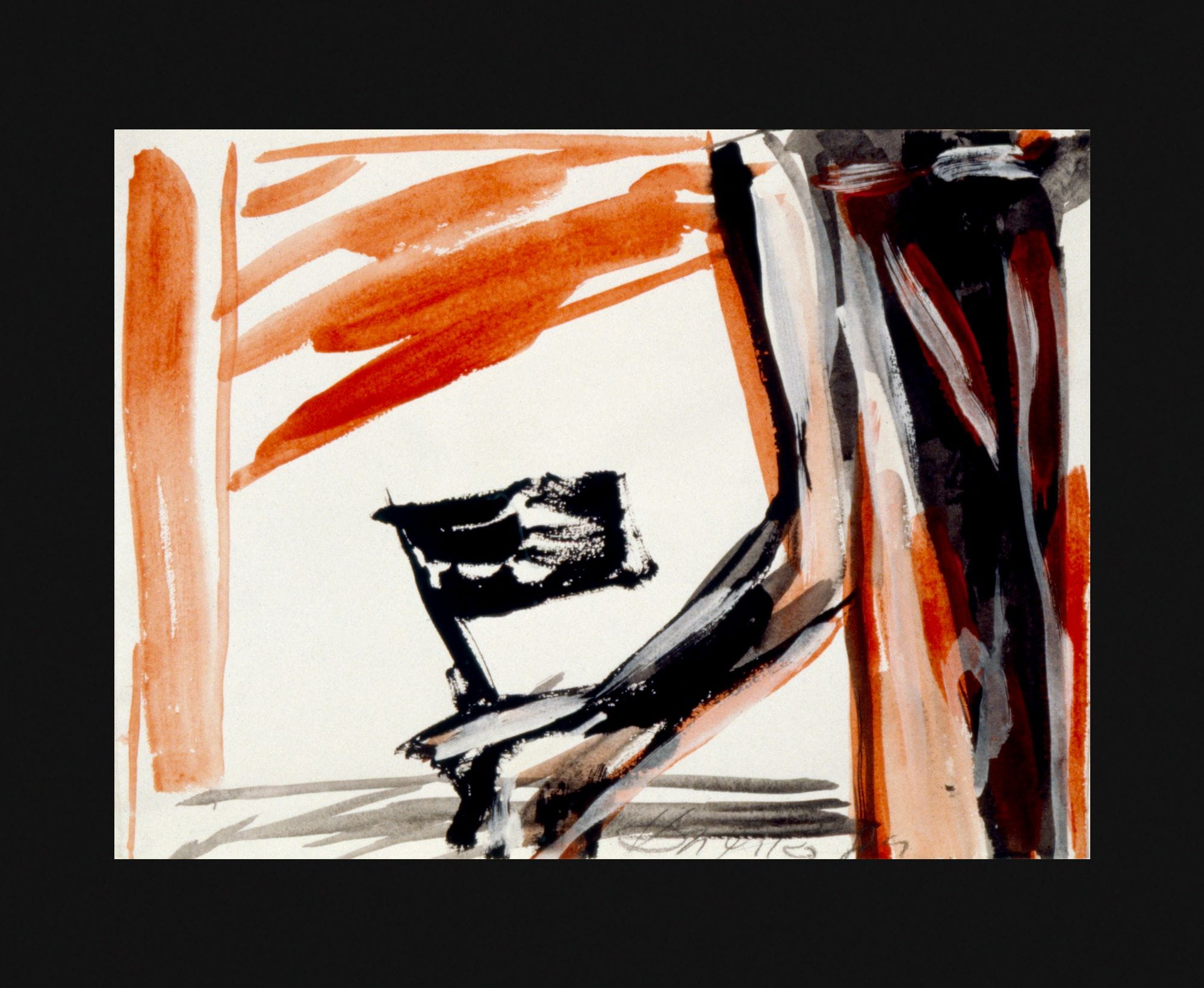

Flags

The artist displayed an interest in the colours of national flags early on (The Scraping of Screens, 1973), and subsequently made references to the form of a banner (Ready for Use, 1980). Later, the flag motif was featured repeatedly, both in objects and in works on paper. Traces of succinct gestures, utilising a narrowed, aggressive palette, are literal anecdotes. A clenched fist with a waving flag (Man with a Flag, 1984) and two triangular pennants pointing at each other (Two Flags, 1982) share an atmosphere of confrontation.

Standing apart in the series are large-scale works made from painted, cut, and torn paper. Enclosed in glass cases (e.g. Flag, 1983), they seem to be taken out of their natural context and bereft of their inherent purpose; petrified in the artistic enclave, they’re standing by.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Flag, 1983

Foil and foam objects

These monumental works, created since 1987, consist of spongy planes and multiple layers of transparent, partially painted foil. The sparing use of means and the airiness of the materials stand in opposition to the complex and multilayered structure — its volume engages the viewer in a game where the varyingly transparent foil prevents ingress.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Foil object at the exhibition in Cologne, Wanda Dunikowski Galerie, Germany, 1989

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Foil Object, Wanda Dunikowski Galerie, Germany, 1989

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Foil Object, Wanda Dunikowski Galerie, Germany, 1989

Given the inability to access the core of the seemingly simple yet intricate object, that sense of depth is paradoxical, and therefore the principle adopted for shaping these forms does not allow to judge their purism or expression. There are, however, noticeable references to the legacies of both non-representational and minimal art (Untitled. Foil Object, 1989), and at times even to ancient iconography (Three Graces, 1989).

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Three Graces, Wanda Dunikowski Galerie, Cologne, Germany, 1989

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, New „New” Revolution, 1985

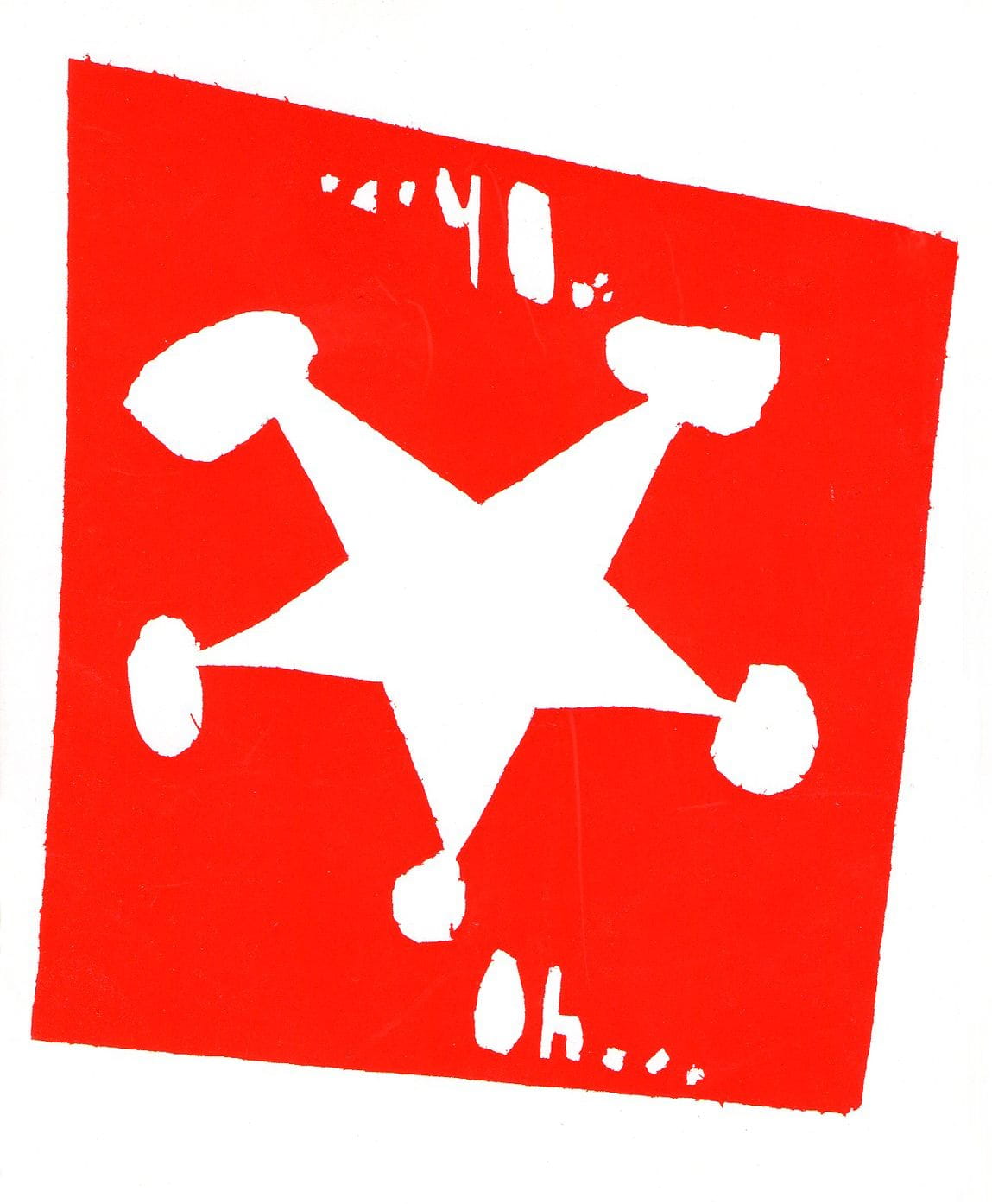

New „New” Revolution

What distinguishes this series, developed since 1983, is the use of a characteristic mark: a pair of overlapping pointed shapes, resembling boomerangs whose implied motions advance in opposite directions. The aggressive symbolism as well as the raw texture, reminiscent of organic matter, correlate with the inflammatory atmosphere of decisive moments in history: the artist worked on this series during the years preceding the opening of the Iron Curtain, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the USSR, and the resulting political transformation in Central and Eastern European countries.

Dealing with abstract ideographs, however, New “New” Revolution goes beyond the artistic attempt to harness political and social change, for at least two different interpretations are conceivable. Firstly, the series is an ironic response to the demand of popular culture for attractively designed signs and emblems, which are not entirely free from ideological features (e.g. Oh… oh…, 1988), and secondly — in view of how the philosophy of art evolved — it comments on the debasement of progress and novelty as the core values of the avant-garde.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, New „New” Revolution, Oh..oh.., 1988

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Heart of New „New” Revolution, 1987

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, The Star (New „New” Revolution), 1988

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, New “New” Revolution, 1983. Galerie Marina Dinkler, Berlin, Germany, 1986

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Current Program XVIII, 1978

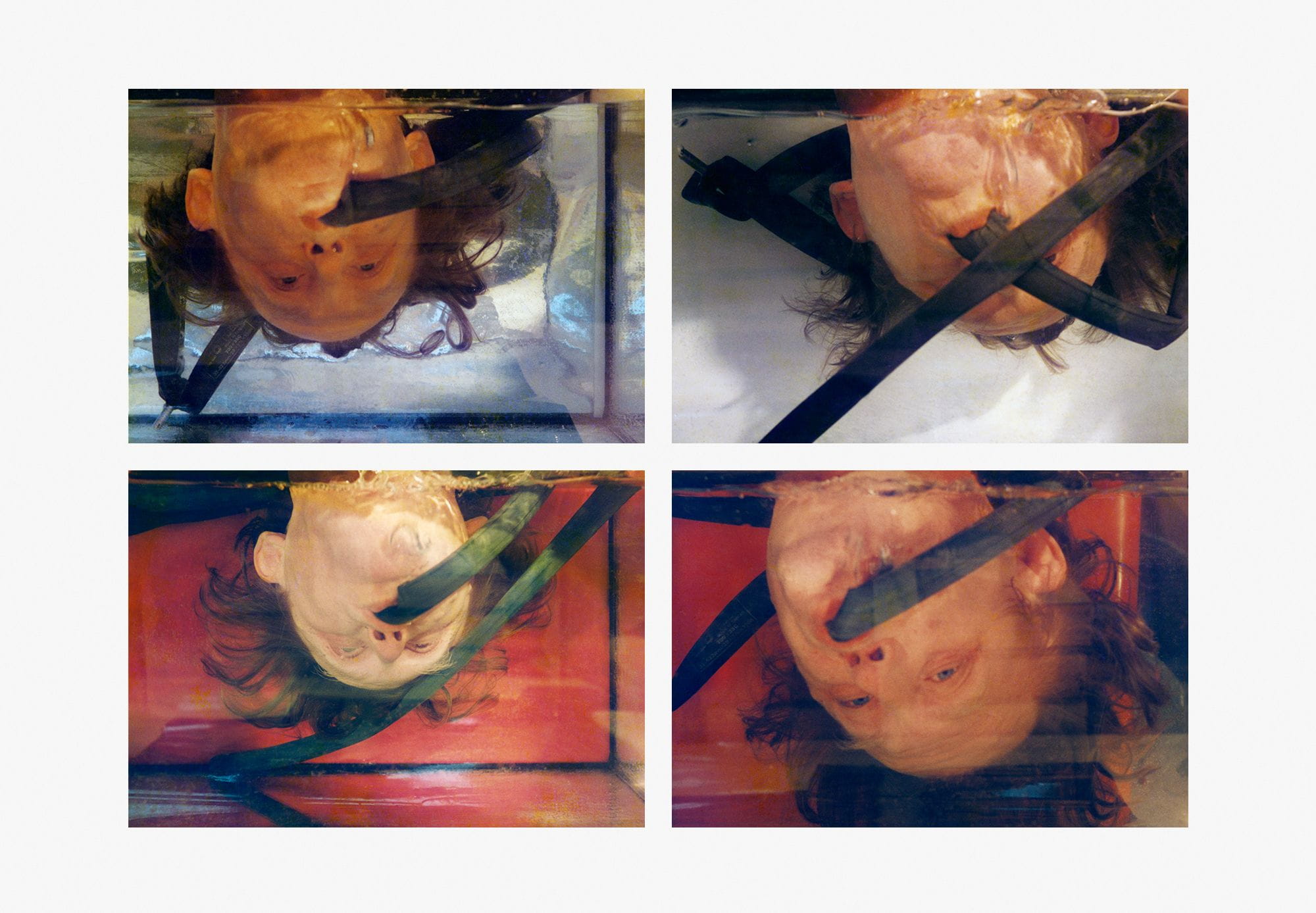

Current Program

In 1974, The Artistic Program Centre Duniko issued the text “MY BEST VIDEOTAPE IS CURRENT PROGRAMME”. This gesture was a direct response to the neoavant-garde artists’ tendency to produce experimental short films. The idea of adopting a television programme — the despised “Dziennik Telewizyjny” (Television News) of the Communist era, for instance — as format and content for a work of art, further evolved in the nineties: based on older instructions, programmatically abnormal installations were constructed from scaffoldings, aquariums filled with water and animal entrails, as well as television sets tuned to the contemporaneous programming; additionally, the televised image was altered by mirrors diagonally affixed to the screens.

The Current Program often adopted the formula of an ironic commentary on the reality shaped and disseminated by the mass media (e.g. Bones Collected from Contemporaneous Battlefields, Against a Backdrop of the Current Program—Truth or Lies?, 1994), or an anecdote with a twist (e.g. Hashish, Marijuana, the Artist’s Skin, and a Lash from Einstein’s Eye, Against a Backdrop of the Current Program—Truth or Lies?, 1994).

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Bones Collected from Contemporaneous Battlefields..., 1994

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Current Program XXVIII, 1993/1994

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Points of No Return, 1992 (at the exhibition at the Bielska BWA Gallery in Bielsko-Biała, 2008)

Points of No Return

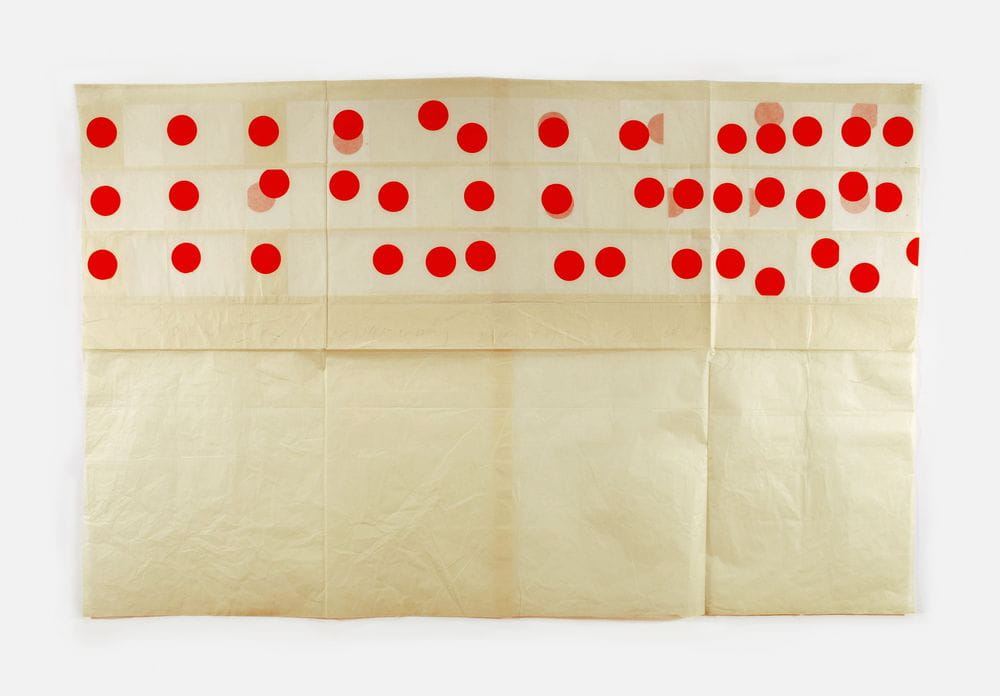

Having employed the form of a large plain dot since the seventies (e.g. Album II A, 1972, or Falling Points, 1985), the artist revisited the idea in the extensive series Points of No Return, developed since 1992.

Arrangements of circles of varying sizes, juxtaposed with a handwritten aphorism which frequently occupied a large portion of the work, render the phrase the point of no return. The series revolves around abstract yet allusive depictions of the stage at which it is impossible to stop an already initiated process, or to prevent or avoid its consequences. Thus a polemical stance has been taken towards the relativity of experiencing and representing reality—or fact versus delusion, for that matter—and a remark has been made, laced with irony, about the logic of the historical development of art.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Pink Point of No Return, 1998. Point of No Return. Retrospektywa. Muzeum Rzeźby Współczesnej w Orońsku, 2002

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Violet Point of No Return, 1998. Exhibition: Galeria Hauck Bonn, Germany, 1999

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Works from the series Points of No Return, 1999. Exhibition: Bonn, Germany, 2000/2001

The Points of No Return, akin to other works by Dunikowski-Duniko which aimed at capturing the essence of a specific process in a given time (e.g. Moment Art) or how the intricate rules governing it are created (e.g. New “New” Revolution), share the formula of disinformation through the use of misleading labels: the red series bears the title Blue Points of No Return (1998); the yellow one, Pink Points of No Return (1992); and so forth. The idea has undergone further transformations, and its reiterations made after 1998, constituting the subseries Stories of Points of No Return, exhibit often grotesque anecdotes involving the points themselves.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Sun Sculpture (1972–1976)

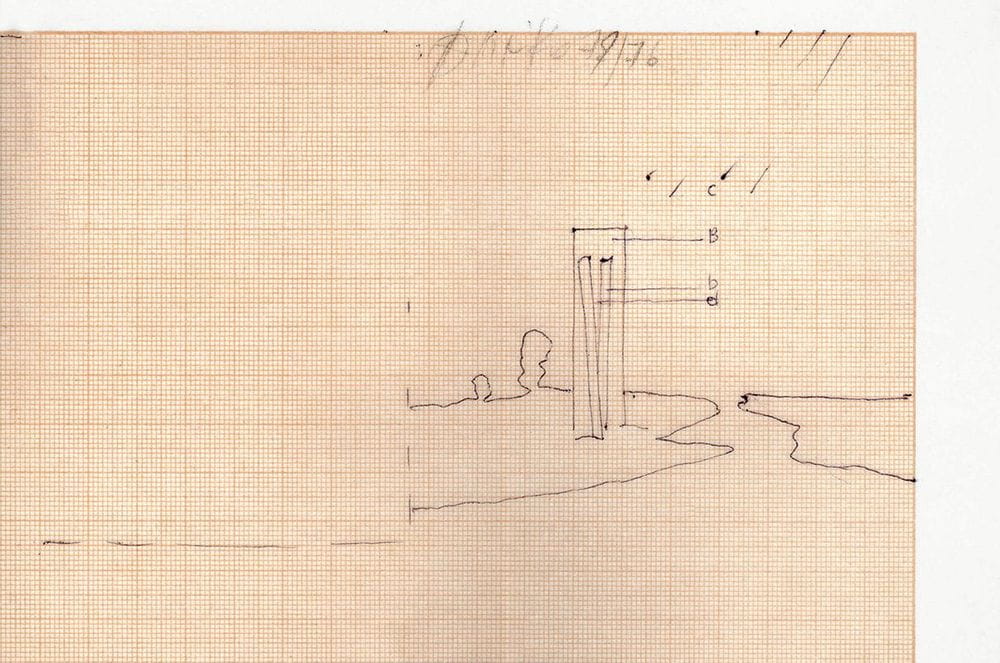

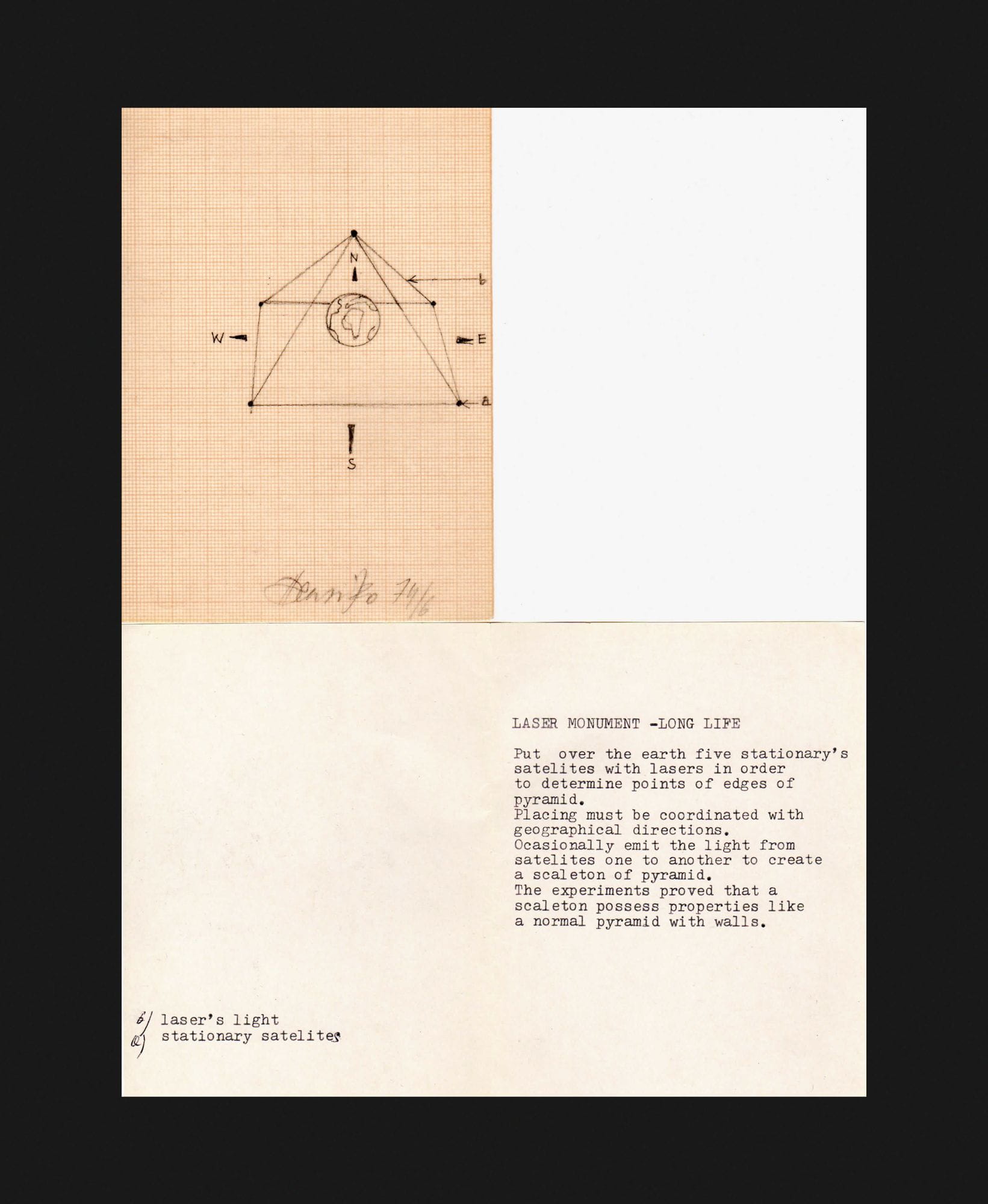

Utopian(?) projects: An Extension of the Life of Mankind, Sun Sculpture, and Pure Light, Pure Love, Pure Death

An Extension of the Life of Mankind (1974–1976) shows the Earth inscribed within the vitalising space of a pyramid, the latter formed by laser beams emitted by five satellites orbiting geosynchronously with the planet around the Sun. The Sun Sculpture (1972–1976), in turn, is a blueprint for an installation in the form of a pipe cut along its length. The mirror-lined interior of the sculpture focuses the light of the sun or the glow of the moon, and the refracted rays shine on a translucent sheet inserted into the central part of the structure.

Neither of these two conceptual projects, sketched on graph paper and presented in 1976 as part of the artist’s application for West Berlin’s DAAD grant, has ever been realised. Decades later, they can be seen as a reaction to other artistic utopias and initiatives aimed at conquering the elements for the purposes of art.

The striving to reach a cosmic dimension, or to act as an advocate of the inexpressible in the arts, is also present in a much later concept, titled Pure Light, Pure Love, Pure Death (1995): the installation allows to immerse one’s senses in infinite depths of the colours white, red, and black, symbolising respectively the light of birth, the heat of love, and the nothingness of death.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, An Extension of the Life of Mankind (1974–1976)

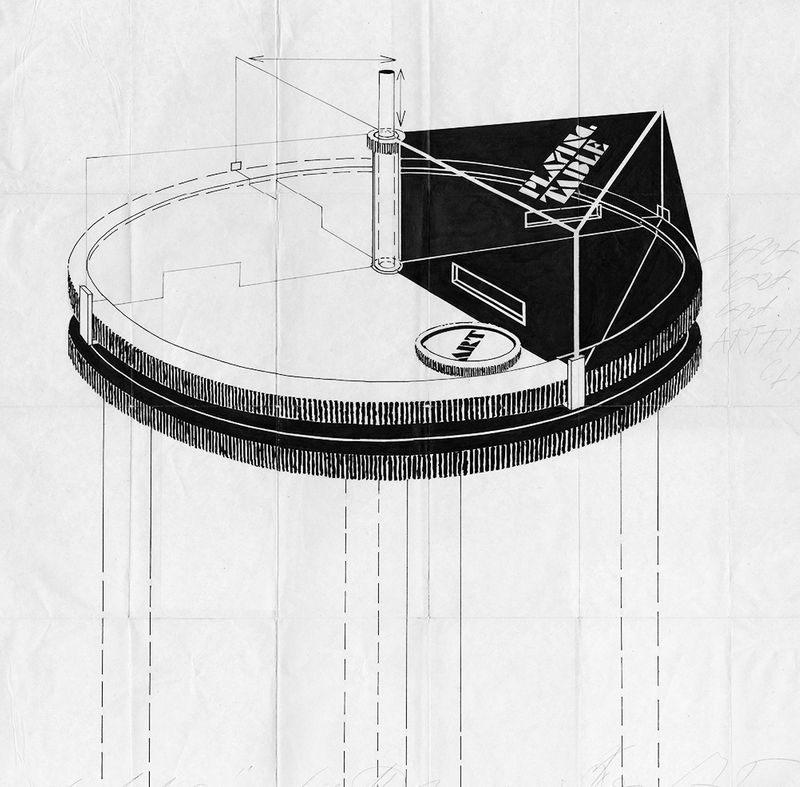

Art Playing Table

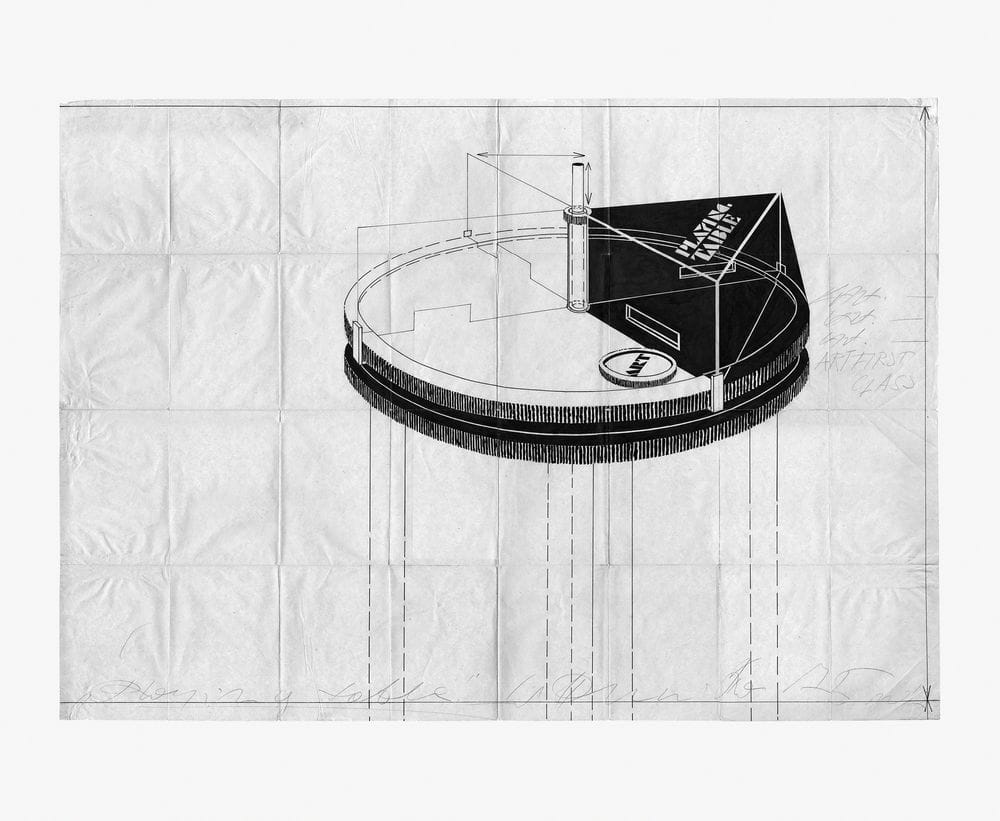

A drawing from 1975 depicts a roulette-like machine: it is a shallow cylinder with a rotating black arm on top—a triangular prismatic container—inscribed with the words “PLAYING TABLE.” On the surface lies a coin marked “ART,” which is never going to reach the apparently dedicated slot in the moving part, because the latter is provided in the wrong place. The structure prompts the viewer to reflect on its workings; both the principle of operation and the deficiencies are accentuated. The mechanism looks like a simple rotating apparatus—but the system, as designed, is actually different from what can be reasoned intuitively. The design thus underscores the incompatibility between the structure and its intended operation—the divergence between the logically deducible movement and the empirically possible one.

Wincenty Dunikowski-Duniko, Art Playing Table (1975)

The Art Playing Table is not a device that could determine any particular movement or process. Inconspicuous compared to many other works, the drawing seems to be an intimate and metaphorical account of matters fundamental to art. Perhaps it is a visualisation of a certain way of formulating artistic ideas, one that defies factual and physical depiction but can at least be signalised.

The concept for an art gaming machine later evolved and came into existence in the form of an installation: television screens embedded in a tabletop displayed footage of splashing red soup and the current television programme (Art Playing Table, 1980/1995).